When it comes to negative information, the first set of questions lawyers often ask are about “how”:

How can I spin this?

How could I present that?

But a better set of questions that better serve transparency to clients is ‘what’:

What happened?

What are the brutal facts?

What are the durable realities?

What is the effect of them?

What can be done to mitigate the situation?

After that, it is completely appropriate to ask ‘why’ and ‘how.’ Root cause analysis techniques definitely have a place — but first ask ‘what.’ In risk assessment terms, the brutal facts are not the peril. The peril is not recognizing them. Recognizing them is what clients expect. It is part of the service they hope you are providing.

REVIEW RELATED TOOL: Facing Reality Checklist

Lawyers, especially trial lawyers, are taught to contend, to stake out a position and argue it. But that needs to be rethought. The business of objective analysis has no room for contention.

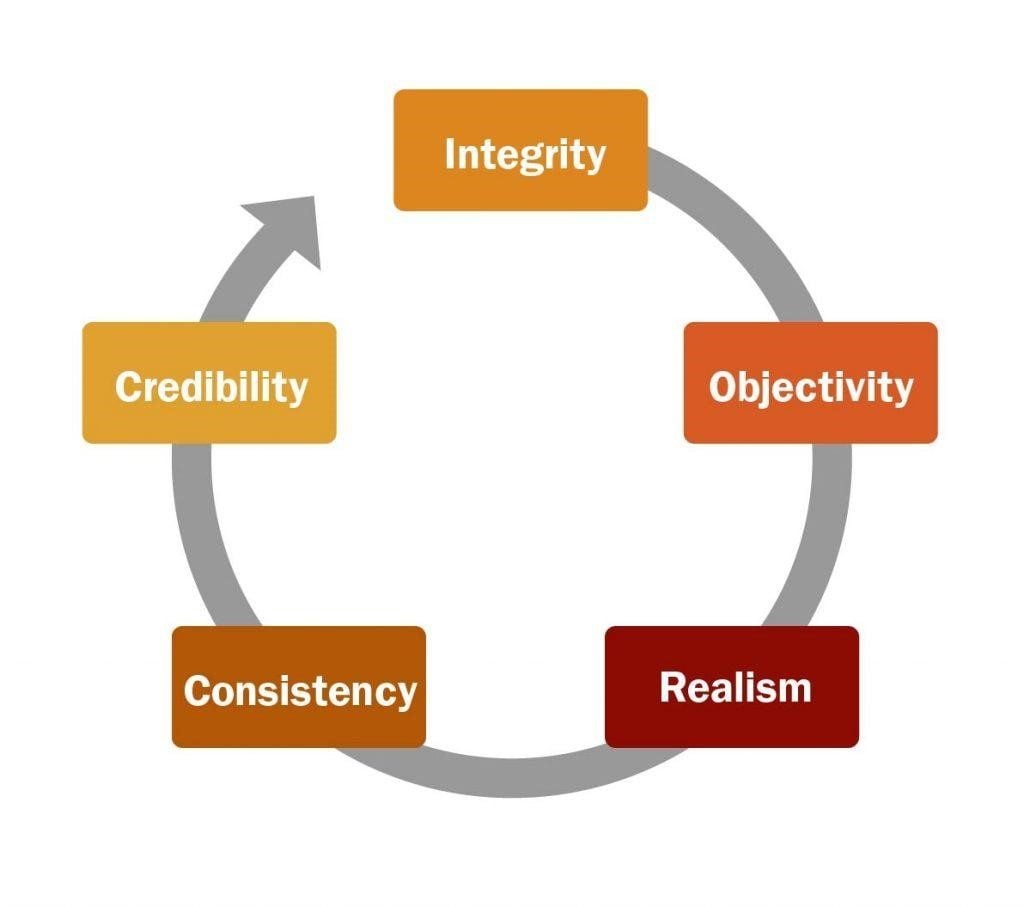

Good execution of a legal project should be a virtuous circle. It’s an approach which starts and ends with integrity, with due prominence given to objectivity and realism.

Even so, it can be an alluring trap for all of us. The psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, author of “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” reminds us that the human brain sometimes works in odd ways and we are not quite as rational, logical decision makers as we might like to think. As lawyers we can all fall into the trap of not analyzing data with enough rigor or objectivity. The temptation to ‘contend’ might come from conditioning, learned behaviors or even our DNA. It doesn’t help that ‘contention’ is not frowned upon. It should be, it’s dangerous. Why? Because you cannot safely run a transaction or fight a case on facts you don’t have or law that should exist.

The exit doors of meeting rooms and courthouses are regularly pushed open by lawyers whose romanticized view of the world has just been displaced by realism. Contention, together with wish-fulfilment, are often the root cause. This practice of contention explains why witnessing a debate between opposing lawyers can sometimes be a dispiriting spectacle, if each is promoting ‘contended realities’ upon the other. But it is deeper than that. By seeking to justify contentions rather than durable realities, we place ourselves at risk of asking the wrong questions and cherishing the wrong points.

This phenomenon is particularly evident for trial lawyers. Trial lawyers have an expression that starting a lawsuit is like making an appointment with the truth. A contentious lawyer who sets about an investigation may well seek nuggets not truths. If encountering a helpful point, the contentious lawyer may seek to exploit, embellish and exaggerate. The lawyer may contend that it’s more than it is and so seek to imbue it with an enhanced reality. If he or she encounters an unhelpful point, he or she may seek to resist it, deny it or spin it. In other words, the lawyer may try to airbrush it out of the picture, in the manner of Ockam’s broom. At the extremes, of course, this led to the infamous shredding episodes at Enron and elsewhere.

Contention, of course, is not to be confused with the legitimate skill of making the best of what you’ve got. To contend is to make the best of what you haven’t got. In individual cases, of course, contention can succeed in beguiling an opponent or a jury. But the approach is fundamentally flawed, it is a ‘set up to fail’ strategy.

Do the right thing Work when it’s time Only do not contend And you will not go wrong

— Lao Tzu, The Art of War, Verse 8

Copyright © 2024 ALM Global, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2024 ALM Global, LLC. All Rights Reserved.