In a closely watched immigration case, the Justice Department urged the U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday to find that immigrants who have been released after serving criminal sentences can be picked up at any time—even a dozen years or more later—and detained without hearings until their deportation cases are resolved.

In his second day on the bench, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, confirmed Oct. 5 after a bruising Senate fight, appeared sympathetic, along with Justice Samuel Alito Jr., to the government’s arguments that federal immigration law does not impose a time limit on when immigration enforcement officials must act after an immigrant is released from criminal custody.

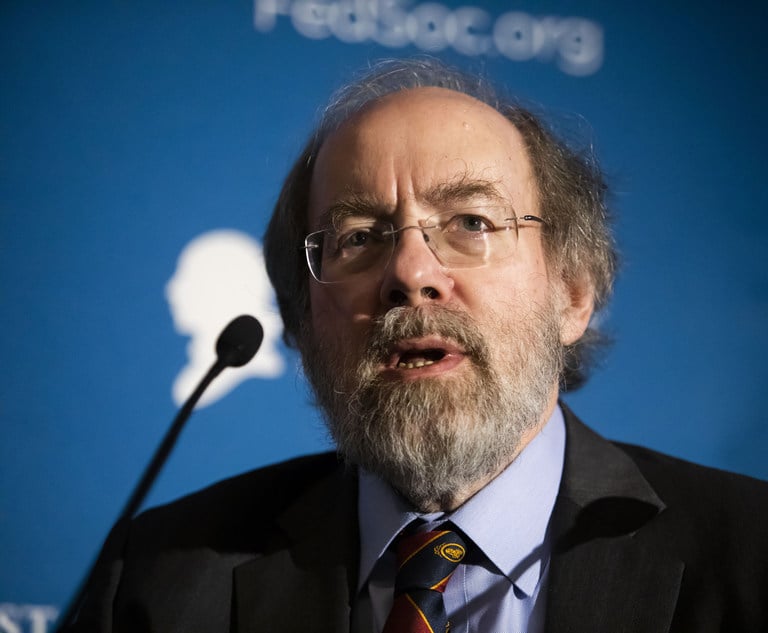

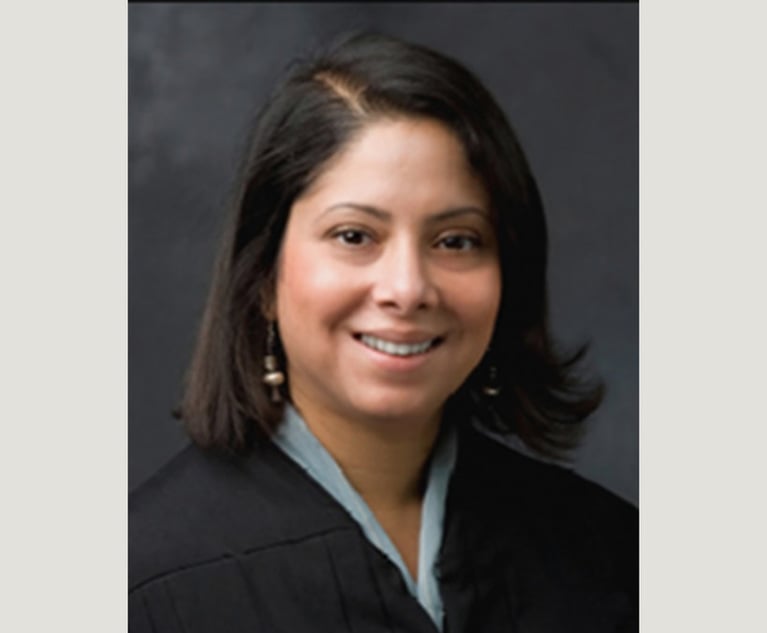

Justice Samuel Alito Jr. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Justice Samuel Alito Jr. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM