International arbitration hearings are primarily about cross-examination. Direct testimony, both from fact witnesses and experts, almost always comes from written statements or reports presented by the witnesses. As we discussed in two columns several years ago, cross-examination of witnesses proffering written statements can involve strategic or tactical decisions, including whether to cross-examine at all. See “Cross-examination in International Arbitration,” NYLJ (March 26, 2007), and “Witness Statements in International Arbitration,” NYLJ (May 27, 2008).

Under English law, going back to the 1894 case of Browne v. Dunn [1894] 6 R 57, a House of Lords case, arguments may be made to a court or jury only if the witness has been confronted in error with the challenge to his or her credibility that testimony of a witness is not credible. That is, the court practice has been that, if a party challenging the evidence of a witness failed to make it plain to the witness, that his or her evidence was not accepted, the judge would have to comment to the jury that one party’s case had not been put, even though the two cases were diametrically opposed. The underlying rationale appears to be a Victorian one—that it is unfair to argue to a court that the testimony of a witness is not to be believed unless the witness has been given the opportunity to respond to the “imputation” of dishonesty.

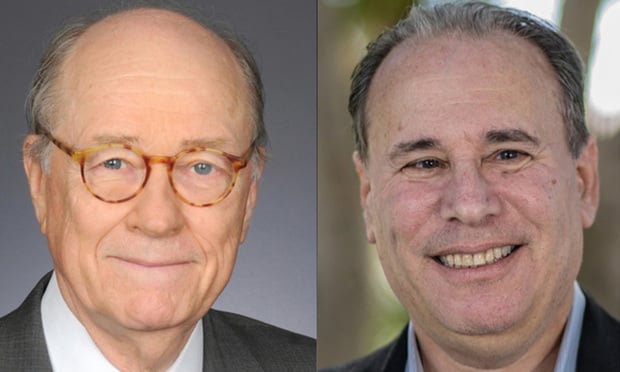

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky