Among the essential rights guaranteed by the First Amendment, “the right of the people peaceably to assemble” seems to garner little distinct discussion, although it is recognized as being inextricably bound with and “equally fundamental” as those of free speech and free press. De Jonge v. State of Oregon, 299 U.S. 353, 364 (1937). Indeed, at least one scholar describes this right as having become “a historical footnote in American political theory and law.” See John D. Inazu, The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly, 84 Tul. L. Rev. 565, 566 (2010). Nonetheless, the right to peaceably assemble for the purpose of advancing beliefs and ideas or “to petition the Government for a redress of grievances” (U.S. Const. amend. I) constitutes an “attribute of national citizenship” (United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542, 547 (1875)).

The importance of the right to peaceably assemble can be found in the traditional characteristics ascribed to its exercise: Often the right is invoked by those who “dissent from the majority and consensus standards endorsed by government” and who seek public, advocacy-oriented visibility (see Inazu, 84 Tul. L. Rev. at 570). The exercise itself tends to be more expressive than simple association, which can be private, and may manifest in parades, demonstrations, and other creative forms of engagement (id.; cf. NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449, 460-62 (1958)).The historical significance of this right, early manifestations of which include eighteenth century political societies and their initially scandalous expressions of open criticism of the federal government, is the “understanding of popular sovereignty and representation in which the role of the citizen was not limited to periodic voting, but instead entailed active and constant engagement in political life” (Robert M. Chesney, Democratic-Republican Societies, Subversion, and the Limits of Legitimate Political Dissent in the Early Republic, 82 NC L. Rev. 1525, 1537-40 (2004); see Inazu, 84 Tul. L. Rev. at 577-81).

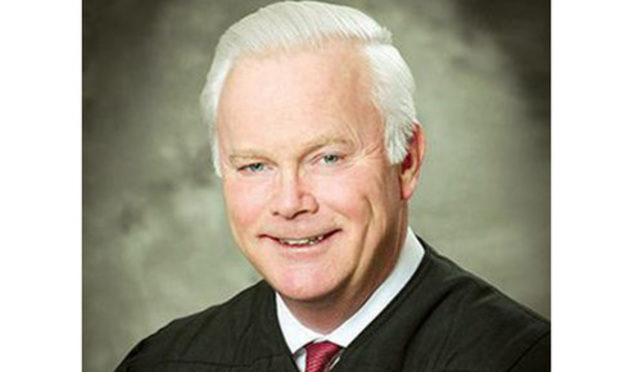

Gerald J. Whalen

Gerald J. Whalen