It would be reasonable to think that, in interpreting foreign law, U.S. courts would accept the statement of a foreign government as to the meaning of its own law. Not necessarily so, according to the U.S. Supreme Court. In this column, we look at that decision and two other significant Supreme Court decisions from this past term in the area of international litigation.

Interpreting Foreign Law

In Animal Science Products v. Hebei Welcome Pharmaceutical Co., Case No. 16-1220 (June 14, 2018), U.S.-based purchasers of vitamin C brought suit alleging that four Chinese corporations that manufacture and export vitamin C had agreed to fix the price and quantity of vitamin C exported to the United States, in violation of §1 of the Sherman Act. The Chinese sellers moved to dismiss the complaint on the ground that Chinese law required them to fix the price and quantity of vitamin C exports, thus shielding them from liability under U.S. antitrust law. The Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China filed an amicus brief in support of the motion, explaining that it is the administrative authority authorized to regulate foreign trade, and stating that the alleged conspiracy in restraint of trade was actually a pricing regime mandated by the Chinese government. The U.S. purchasers countered that the Ministry had identified no law or regulation ordering the Chinese sellers’ price agreement, highlighted a publication announcing that the Chinese sellers had agreed to control the quantity and rate of exports without government intervention, and presented supporting expert testimony.

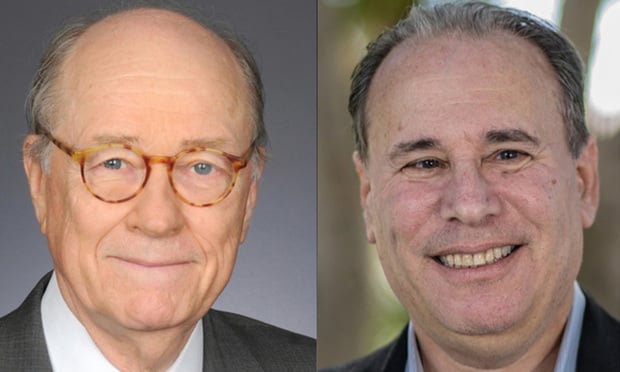

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky