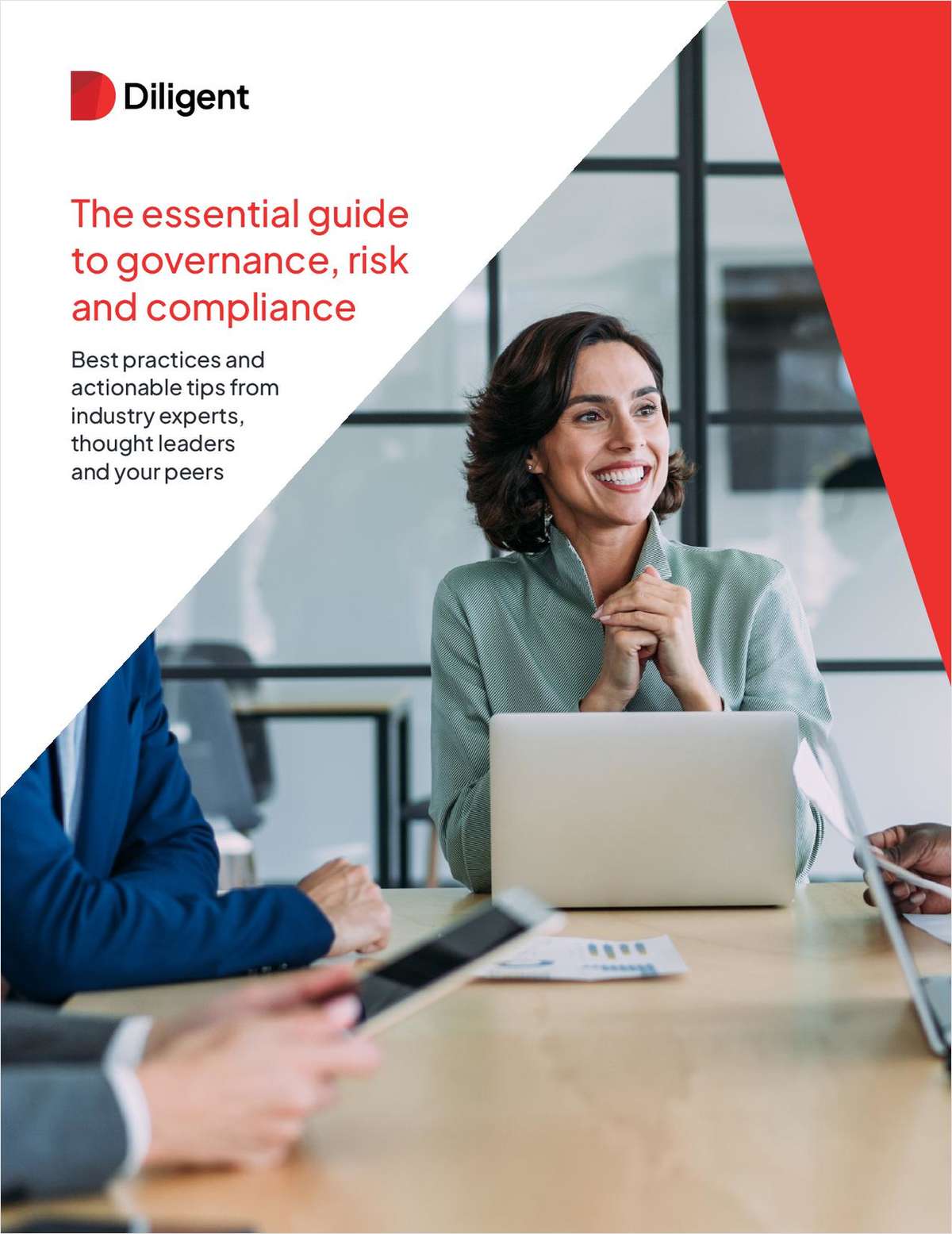

Paul Manafort leaves the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia after a status conference on Nov. 2, 2017. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Paul Manafort leaves the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia after a status conference on Nov. 2, 2017. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALMNew Jury Note Suggests Verdict Is Near in Paul Manafort Trial

Judge Ellis urged the jurors to continue their deliberations and strive for consensus on the 18 charges Manafort is facing.

August 21, 2018 at 12:54 PM

4 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

Nearly two hours into the fourth day of deliberations, jurors in the Paul Manafort trial emerged with a question suggesting they were close to handing down a verdict on the tax and bank fraud charges the special counsel brought against the former Trump campaign chairman.

“Your honor, if we cannot come to a consensus on a single count, how should we fill in the jury verdict form for that count, and what does that mean for the final verdict? We will need another form, please,” the note stated. The note, which was read aloud in court by Judge T.S. Ellis III, was signed by the jury's unidentified foreperson.

Ellis urged the jurors to continue their deliberations and strive for consensus on the 18 charges Manafort is facing. Before the jurors took their seats in the courtroom, Ellis told the prosecution and defense lawyers that he might soon accept a partial verdict if the jurors struggle to reach a unanimous decision on one or more counts.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

Trending Stories

- 1The Law Firm Disrupted: For Big Law Names, Shorter is Sweeter

- 2Wine, Dine and Grind (Through the Weekend): Summer Associates Thirst For Experience in 'Real Matters'

- 3The 'Biden Effect' on Senior Attorneys: Should I Stay or Should I Go?

- 4BD Settles Thousands of Bard Hernia Mesh Lawsuits

- 5First Lawsuit Filed Alleging Contraceptive Depo-Provera Caused Brain Tumor

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250