Back in November 2014, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court revolutionized the products liability landscape in their Tincher v. Omega Flex decision. At the time, we all believed that Tincher was going to redefine products liability law in the commonwealth. We were certain that the Azzarello standard, the artificial distinction between negligence and strict liability, was going to fade to some extent and strict liability defendants were going to be afforded the opportunity to present evidence that was relevant to their defenses. Instead, rather than adopting the Restatement (Third) of Torts, the court surprisingly adopted the risk utility and consumer expectation tests that were first developed in California.

The most important aspect of Tincher is that it raised more questions than it answered about what theories and defenses, trial evidence, and jury instructions would be proper going to infinity and beyond. In particular, Tincher overruled a key component of the prior law—the infamous 1978 Azzarello decision and its rigid “dichotomy” between strict liability and negligence—and replaced it with a “consumer expectations/risk-utility” analysis. This analysis was brand new in Pennsylvania (the clearest analog is California), so our lower courts were asked to create a new body of case law by applying the analysis, defining the burden of proof, and ruling on defenses, evidence, and jury charges in individual cases. Even better, in light of Tincher, there were no longer any valid, recognized instructions to guide juries in determining whether products are defective. Those were to be fought out on a case-by-case basis. Trial courts and lower appellate courts have been dealing with the fallout from Tincher for years and, frankly, despite clear language in the opinion, little has effectively changed.

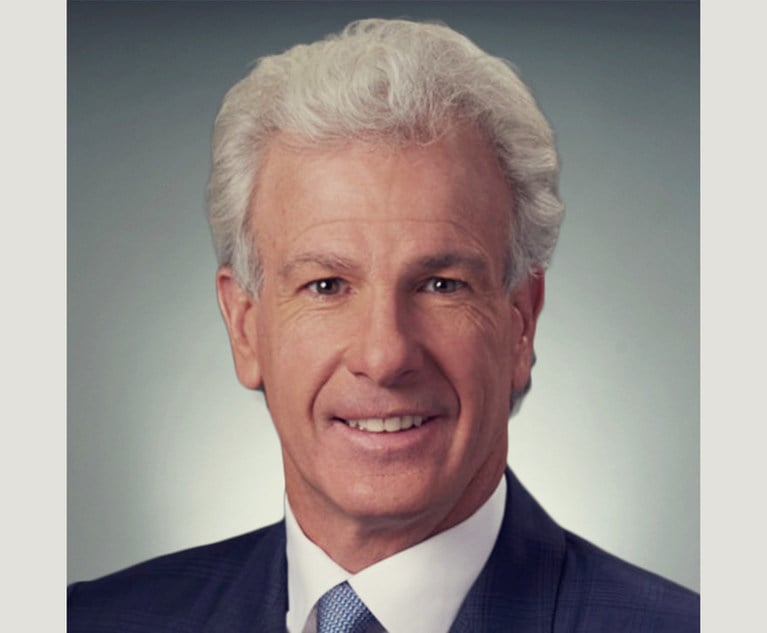

Bradley Remick of Marshall Dennehey. Courtesy photo

Bradley Remick of Marshall Dennehey. Courtesy photo