A jury of nine spoke with one voice. Donald Trump sexually assaulted a woman, brazenly, in a high-end department store, lied about it, and maliciously defamed his victim. To put it mildly, Trump was likely not the easiest client to represent, and his cause not the easiest to defend. But the case warrants a post-mortem to assess the tools of evidence law that may have contributed to the verdict.

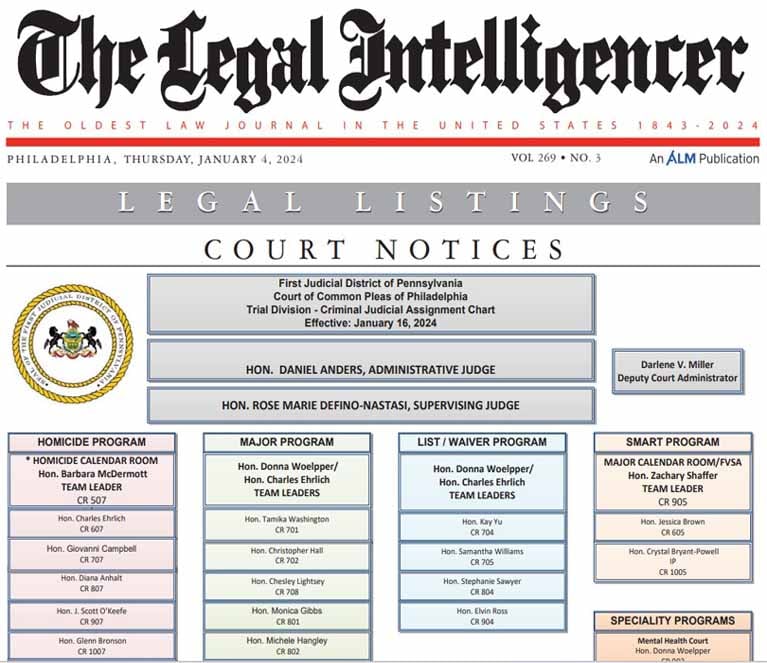

In terms of the power of other acts proof, it was the breadth of Federal Rule of Evidence 415 that gave the plaintiff tremendous corroborative proof. Unlike Pennsylvania law, which bars such proof and restricts proof to evidence of plan, unique modus operandi, or similar noncharacter uses, 415 specifically permits propensity proof, a “did it once, likely did it again” approach restricted to cases of sexual assault and misconduct. More specifically, that rule allows “In a civil case involving a claim for relief based on a party’s alleged sexual assault or child molestation … evidence that the party committed any other sexual assault or child molestation.” “Any” sexual act. No requirement of similar modus operandi; no time-span limitation; no heightened burden of proof. What did that allow here, where the assault proved was said to have occurred in 1995 or 1996?

- Testimony from two other women—Natasha Stoynoff and Jessica Leeds—who say that they were sexually assaulted by Trump and detailed forcible groping and kissing in incidents 36 years apart. One was 1979, the other in 2005; one on an airplane, the other at Mar-A-Lago.

- The infamous Hollywood Access tape from 2005, with the infamous boast ““When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything … Grab ‘em by the p—sy.”

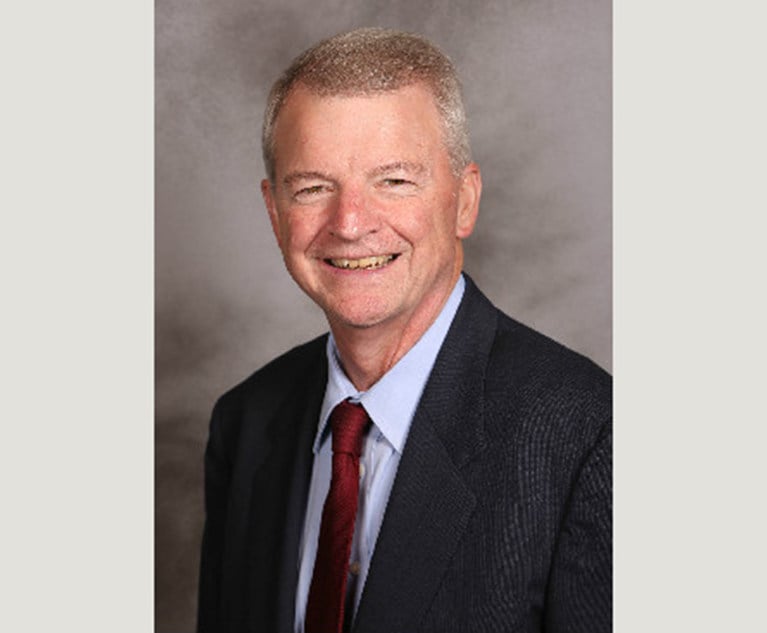

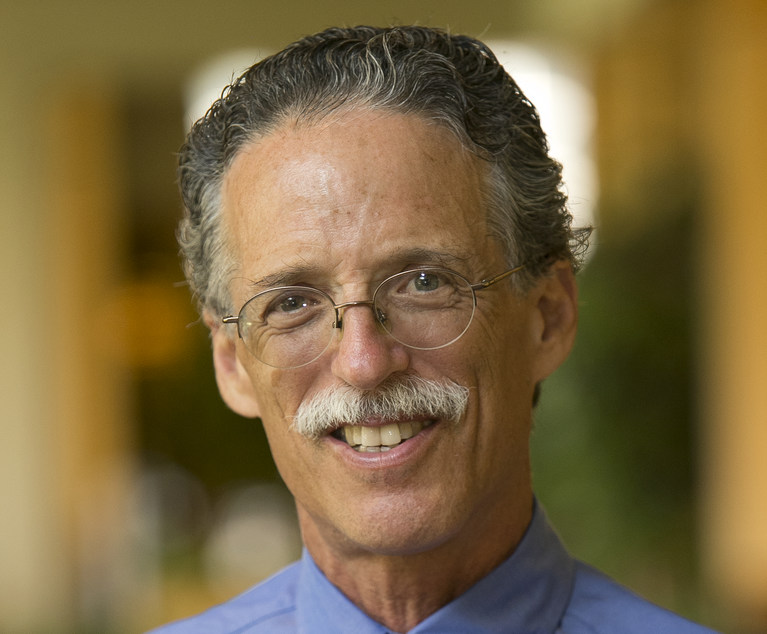

Jules Epstein

Jules Epstein