As the Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently stated, when dealing with hearsay “things can get complicated pretty quickly … At times, the line that divides hearsay from nonhearsay can be difficult to discern.” Nowhere is that more true than with “state of mind” hearsay; but a great deal of clarity has been brought to the issue as a result of the court’s decision in Commonwealth v. Fitzpatrick, Pa., No. 6 MAP 2020 (July 23, 2021).

The problem’s origins are simple. The phrase “state of mind” in evidence law has distinct but oft-conflated definitions. The first simply allows proof of what the person believes or feels when that feeling or belief is relevant. Examples abound:

- “The food at Giuseppi’s is terrible.” If we are trying to prove that the speaker would never eat there, this statement of what the person believes about the cuisine, whether right or wrong, is admissible and is not hearsay.

- “I am Michelangelo, the great sculptor. A snail birthed me.” If we are trying to prove the speaker is delusional/insane, the words tell what the person’s belief is, not that they are the great 16th century artist. The words are not for their truth and thus not hearsay.

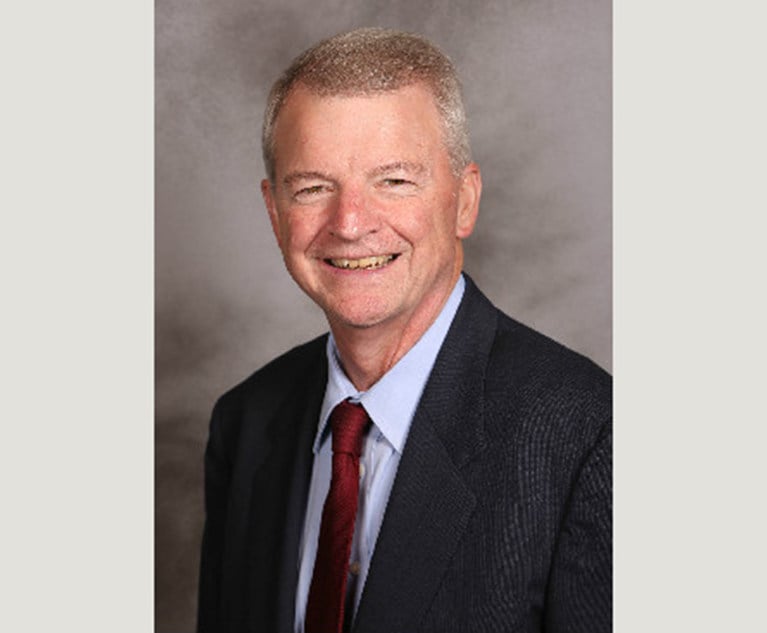

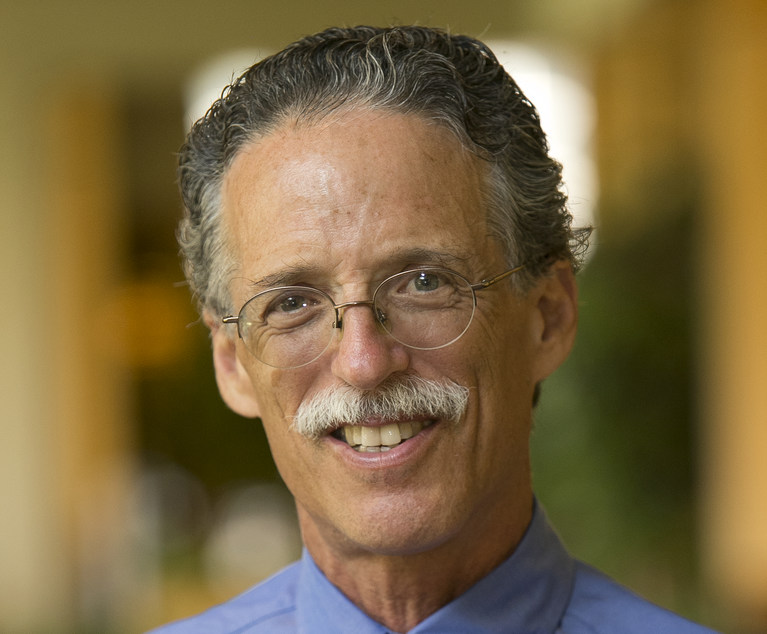

Jules Epstein

Jules Epstein