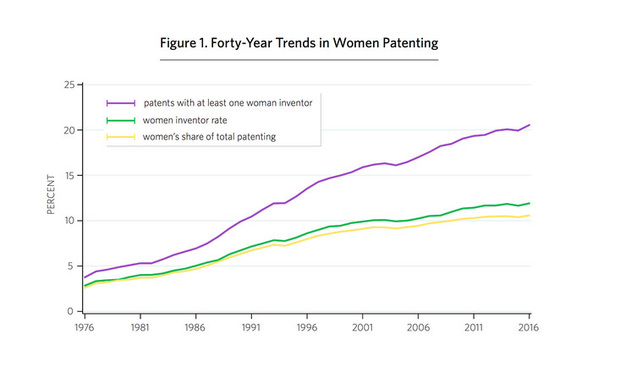

The share of U.S. patents that include at least one woman as an inventor has tripled over the last 30 years. But even with that increase, women inventors still made up only 12 percent of all inventors on U.S. patents granted in 2016.

Those were a couple of headline findings in a U.S. Patent and Trademark Office study released Tuesday. It found that women are making only the smallest of inroads in the patenting space.

Chart from U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

Chart from U.S. Patent and Trademark Office