For a lawyer with a background of trying cases before juries in federal court, as Mr. Newman was doing in the early 1970s, learning about the practice in international arbitration of hearings before three arbitrators, with the contesting parties each appointing one, was a revelatory experience. Instead of planning for the eventuality of presenting to a federal civil jury of six members as triers of fact, counsel had to think, even before commencement of the proceedings, about the composition of a mini jury of one half of that trial court jury—and one that not only would serve as triers of fact but would also rule on issues of law. The power to appoint a tribunal member was a comfort and an opportunity, and of course, was also a power the exercise of which had to take into account that one’s adversary also had the same power.

Time has passed since those earlier days, when the relatively few arbitrations compared to today were carried out with less scrutiny as to the qualifications of arbitrators and their appropriate role in proceedings. Today, with many more commercial and investment arbitrations worldwide, there is greater concern generally about the way such arbitrations are, or should be, conducted. Much is written and discussed in books, journals and conferences and in law school courses and made the subject of institutional rules and guidelines. The qualifications and role of arbitrators have not been spared this scrutiny and analysis.

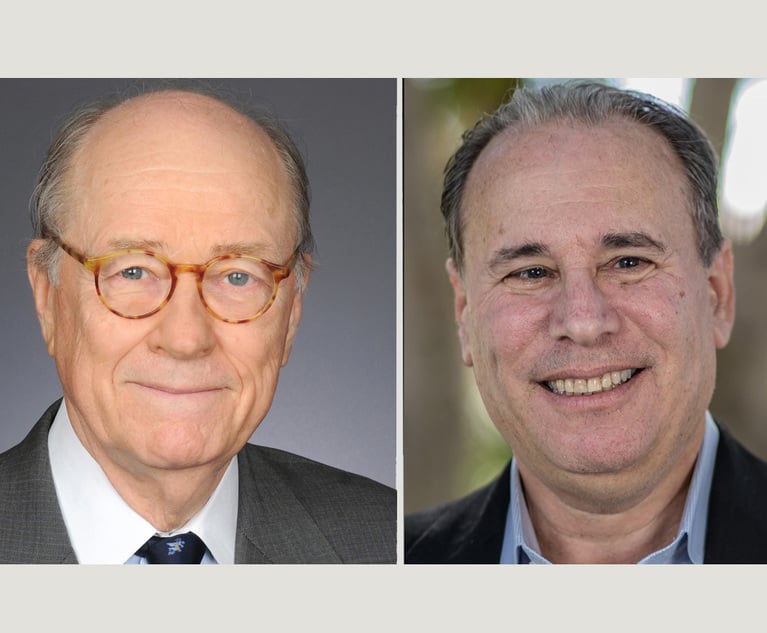

Lawrence W. Newman, left, and David Zaslowsky, right. Courtesy photos

Lawrence W. Newman, left, and David Zaslowsky, right. Courtesy photos