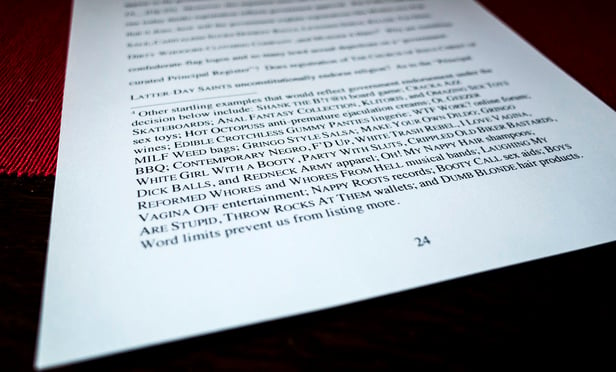

This footnote in the Redskins’ intellectual property fight in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit grabbed some attention.

This footnote in the Redskins’ intellectual property fight in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit grabbed some attention.

A federal agency brief that a Washington judge threw out recently might be memorable for what the court called “excessive” footnotes—48 of them, stretching hundreds of lines. Some footnotes, on the other hand, can linger in a lawyer’s mind like memories of a first love.

We asked a few veteran U.S. Supreme Court and appellate lawyers to share the footnotes that, for them, have stood the test of time. First, however, a little history.

The first published footnote is generally attributed to—or perhaps blamed on—the Elizabethan printer Richard Jugge, who was searching for space for marginal notes about a passage from the book of Job. The space problem was “occasioned by a series of titles and an exceedingly large illustration of a half-naked Job receiving advice from his splendidly adorned friends. Jugge’s solution was to move two of the notes—’(f)’ and ‘(g)’—to the bottom of the page,” according to the 2006 article “Footnote Folly: A history of citation creep in the law.”

The late Judge Abner Mikva of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit once called footnotes in judicial opinions an “abomination.” He confessed he would sneak a peek at some and “I always read footnotes numbered 4.” That’s likely a reference to what’s been described as “the most important footnote in constitutional law”—Footnote 4 in United States v. Carolene Products, the 1938 ruling that applied a presumption of constitutionality to economic regulations.

Mikva’s essay included a single footnote: Footnote 4. There was no 1, 2 or 3. And that lone footnote said this: “Just what did you expect to find?”

What follows are recollections, edited for length and clarity, from several lawyers about memorable footnotes.

‘We Are Honored’

Remembering a stand-out footnote was “easy” for Roy Englert Jr. of Robbins, Russell, Englert, Orseck, Untereiner & Sauber: Footnote 7 in the 1992 case he argued American National Red Cross v. S.G. Justice David Souter, writing for the majority, said there: “The dissent accuses us of repeating what it announces as Chief Justice Marshall’s misunderstanding, in Osborn, of his own previous opinion in Deveaux. We are honored.”

The ‘War of the Dogs’ Footnote

Kannon Shanmugam recalls a lengthy footnote from his clerkship year with Justice Antonin Scalia. The Williams & Connolly partner called it the “war of the dogs” between justices Souter and Scalia over the meaning of the word “revoke” in the 2000 case Johnson v. United States.

Souter wrote in Footnote 9:

When text implies that a word is used in a secondary sense and clear legislative purpose is at stake, Justice Scalia’s cocktail-party textualism must yield to the Congress of the United States. (Not that we consider usage at a cocktail party a very sound general criterion of statutory meaning: a few nips from the flask might actually explain the solecism of the dissent’s gunner who “revoked” his bird dog; in sober moments he would know that dogs cannot be revoked, even though sentencing orders can be. His mistake, in any case, tells us nothing about how Congress may have used “revoke” in the statute. The gunner’s error is, as Justice Scalia notes, one of current usage. (It is not merely that we do not “revoke” dogs in a “literal” sense today, as Justice Scalia puts it; we do not revoke them at all.) The question before us, however, is one of definition as distinct from usage: when Congress employed the modern usage in providing that a term of supervised release could be revoked, was it employing the most modern meaning of the term “revoke”? Usage can be a guide but not a master in answering a question of meaning like this one. Justice Scalia’s argument from the current unacceptability of the dog and ox examples thus jeopardizes sound statutory construction rather more severely than his sportsman ever threatened a bird.