Last week, the California Supreme Court issued its ruling in Troester v. Starbucks, and departed from federal law’s more employer-friendly version of the de minimis rule, which it characterized as stuck in the “industrial world.” In holding that Starbucks Corp. must compensate hourly employees for off-the-clock work that occurs on a daily basis and generally takes four to 10 minutes after the employee clocks out at the end of their shift, the California justices announced they were ensuring California law was in line with the modern technologies that have altered our daily lives. De minimis means something is too minor or trivial to take into account, and the court clarified what is trivial and what is not.

Prior to the court’s ruling, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit had requested that the California Supreme Court answer an unsettled question under California law regarding the de minimis doctrine and its availability as a defense for wage claims under the California Labor Code. The court’s ruling sets the applicability of the de minimis defense at odds with its application under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), where the defense is recognized more broadly. Further, although the decision does not foreclose employers from raising defenses to wage claims based on circumstances where recording time would be difficult, today’s ruling does place employers at risk for greater exposure to claims and penalties for time spent on tasks that are not compensable under the federal de minimis rule.

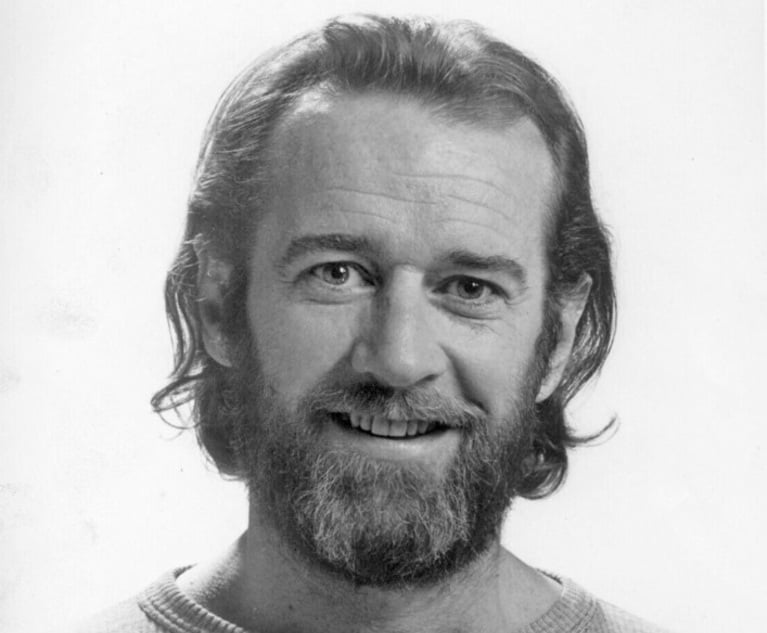

David E. Amaya, partner with Fisher & Phillips, in San Diego. (Courtesy photo)

David E. Amaya, partner with Fisher & Phillips, in San Diego. (Courtesy photo)