Photo by Aaron Couture/Fotolia

Photo by Aaron Couture/Fotolia

Lawyers filing dozens of lawsuits over the opioid crisis have taken a page out of the Big Tobacco playbook—but not the whole book.

The lawsuits bear many resemblances to the litigation against Big Tobacco, which ended with a $246 billion settlement in 1998. The underlying claims are the same: A group of corporations conspired to conceal the dangers of an addictive drug that’s led to a public health problem. Some of the same lawyers have been hired on a contingency fee basis as outside counsel to bring cases on behalf of governments.

But there are significant differences. Unlike tobacco, which focused primarily on four primary defendants, the opioid cases name dozens of companies and individuals with varying alleged roles in the crisis, from drug manufacturers and distributors to doctors and clinics. And while state attorneys general led the tobacco litigation, cities and counties have spearheaded the opioid cases.

That means it might be highly problematic to negotiate a big settlement with everyone on the table.

“The same cast of characters on the plaintiffs side are involved—although one big difference in terms of plaintiffs is in addition to state governments, you’ve got cities and counties also doing this, which would greatly complicate prospects of a settlement,” said Richard Ausness, a professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law. “Who knows how it will turn out, but it’s going to be much more complex than the tobacco cases.”

But Joseph Rice, whose firm, Motley Rice, represents the state of New Hampshire and the city of Chicago in their opioid suits, said cooperation would come. “As this progresses, I think everyone will realize the benefit of cooperation,” he said.

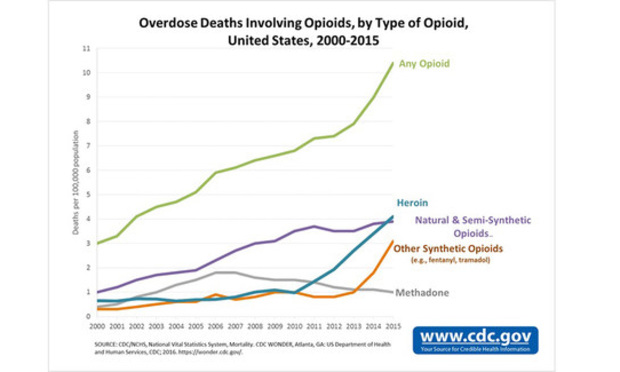

Opioids, which are prescription painkillers that include Percocet and OxyContin, have led to a rise in overdoses and addictions. More than 183,000 people have died of opioid overdoses from 1999 to 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. On Oct. 26, President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency—but he stopped short of granting additional funds to combat the problem.

CDC

CDC

In courts across the country, more than 100 lawsuits have been brought by states, cities and counties. Most were filed in the past four months, primarily in states with the highest prescription rates, like West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio.

Lawyers who crafted the tobacco deal have jumped into the fray, including Rice, Steve Berman of Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro and former Mississippi Attorney General Mike Moore. But there’s disagreement about how the cases should proceed. West Virginia attorney James Peterson of Hill, Peterson, Carper, Bee & Deitzler, who has brought nearly half the federal cases, moved last month to coordinate all the opioid lawsuits into a multidistrict litigation proceeding. He’s joined by some big names: Russell Budd of Baron & Budd and Mike Papantonio of Levin Papantonio Thomas Mitchell Rafferty Proctor. He’s gotten some pushback from his colleagues in the plaintiffs bar, many of whom have cited a need to keep the cases local.

It’s already a different start than in tobacco, where “there was a fair amount of cooperation among the AGs and the law firms handling the litigation,” Ausness said. “Here, it’s more like an Oklahoma land rush, all trying to jump on the bandwagon, and not a bunch of cooperation.”

An MDL might be necessary to manage an ever-growing caseload, said Baron & Budd’s Burton LeBlanc. “It’ll be unwieldy and duplicative and very expensive,” he said. “I would hope the lawyers would at least organize and coordinate their efforts to hold the industry accountable.”

The U.S. Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation is set to hear arguments on an MDL at its Nov. 30 hearing in St. Louis.

Here are three major takeaways at this early stage of the litigation:

Cities and counties, not states, are spearheading the litigation.

Unlike in the tobacco cases, the state attorneys general aren’t out in front of the litigation. So far, attorneys general in 10 states, including New Jersey’s filing this month, and the Cherokee Nation have filed suits this year.

But cities and counties are the leading edge, because they are dealing with the costs of opioid addicts on a regular basis.

“Some state attorneys general have taken no action that is visible to the public, and this is a very emotional issue at the local level,” said Rice. “When you go to a City Council meeting or a town hall meeting or a budget control meeting or a police safety meeting, the odds are somebody at that meeting has had a bad experience personally with a friend or neighbor or a colleague recently. These are small town, hometown people who are impacted.”

And cities and counties have borne the brunt of the cost: Hospitalization and detention of drug addicts, treatment programs, overtime pay for police officers to patrol the streets. The tobacco cases, in contract, focused on the Medicaid payments that states paid for illnesses tied to smoking.

“Unfortunately, all that human misery is met with a high financial cost associated with it: health care costs, criminal justice costs, lost productivity,” said Jeffrey Simon of Simon Greenstone Panatier Bartlett, who represents two Texas counties in their opioid suits. “It makes perfect sense that counties and cities would want to combat this in a personal way because it is felt so personally.”

Almost all of the cities and counties have hired outside counsel, which could be a sticking point going forward. Some lawyers, like Simon, cited those contracts in opposing an MDL, where attorneys from a different firm would spearhead the opioid litigation even though cities and counties hired their preferred outside counsel on a contingency basis.

“When a county in Texas hires outside counsel they do it through their commissioner’s court,” Simon said. “They didn’t hire some group of lawyers that they never met with or counseled with to guide their lawsuit in some distant state. That is not what they took on to do on behalf of their citizens.”

Lots of defendants.

Lawyers have taken different approaches over who to sue. Some name manufacturers, some distributors—some both. Some list a dozen defendants, while others have sued just one company. Some suits even name clinics that provided the pills, as well as doctors who authored articles supporting the safety of opioids for chronic pain.

Most of the initial suits targeted one of five opioid manufacturers: Purdue Pharma, Teva Pharmaceutical Ltd., Johnson & Johnson and its subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Endo Health Solutions Inc. and Allergan. Some of those manufacturers already have settled false marketing claims in previous cases.

But the new cases have focused on a new target: The three primary wholesale distributors, AmerisourceBergen Corp., Cardinal Health Inc. and McKesson Corp. Those cases, in which many of the manufacturers have since been added, allege the distributors failed to flag to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration “suspicious orders” of opioids under the Controlled Substances Act.

The distributors, many of which have agreed to pay millions of dollars in regulatory fines over similar conduct, were the focus of a “60 Minutes” episode that aired this month.

“The biggest difference is in tobacco you had a product that was manufactured, marketed, sold and placed by one party,” Rice said. “Here, you’ve got manufacturers that are separate from distributors that are separate from wholesale houses, separate from mass sellers. Then you’ve got the doctors. So you’ve got a whole different complexity in this case that you didn’t have in tobacco. There’s going to be a lot of finger-pointing.”

In statements to Law.com, many of the defendants were quick to point out that their products contributed a small percentage of the total market share of opioids.

In an email, John Parker, a spokesman for the Healthcare Distribution Alliance in Arlington, Virginia, speaking on behalf of the distributors named in the opioid cases, said “we aren’t willing to be scapegoats.”

“We don’t make medicines, market medicines, prescribe medicines, or dispense them to consumers,” he wrote. “Given our role, the idea that distributors are solely responsible for the number of opioid prescriptions written defies common sense and lacks understanding of how the pharmaceutical supply chain actually works and how it is regulated.”

The primary defendants are unified about supporting an MDL—though in various venues.

The distributors, based in Ohio, Pennsylvania and California, want the cases to go to U.S. District Judge David Faber of the Southern District of West Virginia, who is overseeing 16 cases.

The manufacturers, based in Connecticut, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, want the cases in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, where U.S. District Judge Jorge Alonso has wiped out much of the city of Chicago’s case against opioid manufacturers. The manufacturers also recommended districts in New York and Pennsylvania.

The claims aren’t the same.

The opioid cases allege “almost eerily parallel conduct” that was brought against the tobacco industry, said Berman of Hagens Berman, who represents the city of Seattle, the state of Ohio and the two California counties in opioid suits.

In general, the claims accuse the defendants of making a product that is additive and marketed to be safe. Some cases have brought claims under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, but most focus on state consumer fraud statutes, negligence and public nuisance allegations.

Still, Berman also acknowledged one difference.

“There’s a financial difference here in that the tobacco companies were enormously profitable and going forward were going to be enormously profitable,” he said. “The biggest culprit in the opioid epidemic is Purdue and they’re not anywhere near the financial strength of the tobacco companies. So the big question mark in all this litigation is there enough money out there to help solve the problem?”

The defenses also could be different this time. Unlike tobacco, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has regulated opioids since 1970, and the drugs carry a warning about potential addiction.

“Tobacco wasn’t regulated the way drugs are,” Ausness said. “And so that could be an important difference. They would say our products were vetted by the FDA.”

In statements responding to the lawsuits, defendants Purdue Pharma, AmerisourceBergen and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, cited FDA approval of opioids in their denials of the allegations.

AmerisourceBergen spokesman Gabe Weissman called the comparisons to the tobacco litigation a “flawed analogy.”

In some cases, the manufacturers have filed motions to dismiss, insisting that the lawsuits fail to name specific sales representatives or doctors who pushed excessive amount of opioids on patients.

In the Chicago case, for instance, Alonso found that the complaint lacked those specifics in dismissing some of the claims.

“There was a certain amount of parallel conduct,” Ausness said. “But in the absence of some kind of incriminating document, I don’t know if there is or there will be some kind of smoking gun type of document like there was in the tobacco companies.”

Rice acknowledged the discovery challenges.

But, he quickly retorted: “Let’s flip it around.” He mentioned recent federal indictments, such as a Rhode Island doctor who admitted accepting kickbacks from manufacturer Insys Therapeutics Inc. in exchange for writing prescriptions. And on Oct. 26, federal prosecutors charged the founder of drug manufacturer Insys Therapeutics, which was named in cases brought by the states of New Jersey and Arizona. That’s on top of six other former Insys executives who have been charged with bribing doctors and defrauding insurance firms.

And, last week, Bloomberg LP reported that prosecutors in Connecticut have opened a criminal probe of Purdue.

“We didn’t have that in tobacco,” Rice said.