At the Grammy Awards this past month, the music world celebrated the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip-hop music. Started in the 1970s in urbanized areas of New York City, rap music became a musical and cultural phenomenon that became the voice for many marginalized Black Americans with roots to Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. The music traces its roots to heavy rhythmic percussion, mixed with precise spoken word delivered over hard drum beats. Hip-hop culture is inextricably intertwined with economic, social, cultural and political issues of the day, particularly in disadvantaged or underserved urban communities.

The earliest forms of hip-hop were heavily influenced by political upheaval and the civil rights movement. Speaking to everyday issues, such as poverty, gangs, crime, family, social status, and anything else in life, hip-hop became a counterculture to mainstream America. The music represented a safe space for rappers, DJs, graffiti artists, breakdancers and bootleggers. Hip-hop has been called the central cultural vehicle for open social reflection on poverty, fear of adulthood, the desire for absent fathers, frustrations about Black male sexism, female sexual desires, daily rituals of life as an unemployed teen hustler, safe sex, raw anger, violence and childhood memories. In short, (hip-hop) is Black America’s most dynamic contemporary popular cultural, intellectual and spiritual vessel. See Rose, Tricia, “Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America,” New Hampshire: University of New England Press, 1994. There has long been a discussion of violence and misogyny in rap music. In its rarest and rawest form, rap lyrics are delivered in a braggadocious way, and at times can incorporate lurid, misogynistic themes. It’s not uncommon to hear rap lyrics describing women as “bitches” and “hoes.” Women as objects of sexual gratification and the imaging of violence against women can be a reoccurring theme for some rappers. The explanations for this objectification are as diverse as the culture itself. Ranging from toxic masculinity to mainstream attitudes toward women, no one theory can explain the existence of crime and misogyny in hip-hop culture. For a more scholarly analysis on violence in hip-hop, one should read “Code of the Streets,” by renowned sociologist and ethnographer, Elijah Anderson. Anderson writes that violence is so much a part of these disadvantaged communities that a set of informal rules, which polices personal and group behaviors, has been established and many of the lyrics in rap music reflect a code of the street. See Anderson, Elijah. 1994, “Code of the Streets,” Atlantic Monthly 273(5): 81-94.

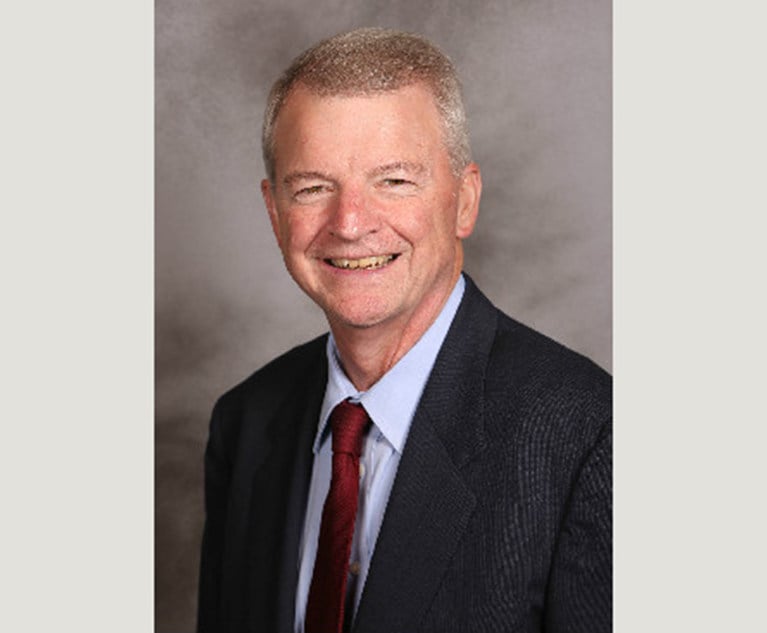

Jeffrey Campolongo, of Law Office of Jeffrey Campolongo.

Jeffrey Campolongo, of Law Office of Jeffrey Campolongo.