The heated battle over redistricting in Pennsylvania is the culmination of more than a year of roiling tensions between what some view as a brash and inexperienced state Supreme Court and a legislature that views the court as a political enemy that must be brought “to heel”—and it could get much worse, attorneys and other observers said.

“It’s open war now. It’s on,” said one lawyer familiar with both the state Supreme Court and the legislature. “It was waiting for an outlet.”

While everyone seems to agree that the intensely politically divisive issue of redistricting has heightened the animosity between the majority Democratic high court and the Republican-controlled General Assembly, some observers traced the friction back to a source that, at least on its face, appears to have little to do with partisan politics.

“Part of the problem with this Supreme Court is the new people who are aggressive don’t understand government as well as the more institutional justices,” the attorney with knowledge of the court and legislature said.

Ronald Castille, the chief justice of the court from 2008 to 2014, agreed.

“There are new people on there that really aren’t aware of the impact of what they can order and what they can do. It’s always a very delicate balance of power with the legislature and the governor and the courts,” Castille said.

Castille said the court is the weakest branch, which has to stand on its reputation much more so than the other two, so it must work harder to convince the other branches to get on board with it.

“The legislature is going to moan and groan, but you’ve got to work with them. You can’t just tell them what to do,” he said. “There’s a give and take.”

On the flipside, however, others said they viewed the justices as increasingly under attack by aggressive and territorial legislative leadership that regards the court as its Democratic nemesis.

“What it comes down to, essentially, is we have three co-equal branches of government but the legislative leadership and House and Senate basically look at the court system as an agency they need to bring to heel. … Marbury v. Madison hasn’t bubbled through to them yet,” said another lawyer familiar with the Supreme Court and the legislature.

The lawyer added: “This group, the leadership now in the legislature, is exploring to a greater extent than I’ve seen in my career whether they can bully the court. … They view the court as a political body now as opposed to an independent judiciary.”

Scott B. Cooper, a Harrisburg personal injury attorney who has chaired the Pennsylvania Association for Justice’s legislative policy committee, took particular issue with the blowback the court has received from some lawmakers over the Jan. 22 decision to invalidate Pennsylvania’s congressional map.

“They’re doing their job and they’re being criticized unfairly,” Cooper said of the justices.

There’s no denying the court has undergone a major transformation over the past two years, with former Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas Administrative Judge Kevin Dougherty and former Superior Court Judges David Wecht and Christine Donohue, all Democrats, joining in January 2016 and Republican former Superior Court Judge Sallie Updyke Mundy coming aboard in July of that year. The only remaining veterans on the court are Chief Justice Thomas Saylor and Justices Max Baer and Debra Todd. Saylor is a Republican and Todd and Baer are both Democrats.

By the fall of 2016, some of the new justices began to assert themselves in ways that rankled lawmakers.

On Sept. 28, 2016, the court assigned the legislature with tasks and deadlines in two cases—one dealing with oil and gas regulations, another with casino taxes. The court ordered stays on portions of its decisions to allow the passage of remedial measures to fix the statutes under review, and placed unusual sunsets on the stays.

In Robinson Township v. Commonwealth, the justices struck down Section 3218.1 of Act 13, the state’s oil and gas law, finding that it constituted a “special law.” It had required the Department of Environmental Protection to notify citizens using public water systems of a chemical spill, but excluded the roughly 3 million Pennsylvanians using private wells from notification. The court directed the legislature to enact “remedial legislation” within 180 days to avoid the elimination of notice to both public and private water sources.

In Mount Airy #1 v. Pennsylvania Department of Revenue, the justices ruled unconstitutional the state’s mechanism for assessing local taxes on non-Philadelphia casinos’ slot machine revenue. The statute violated the uniformity clause of the state constitution because it created variable tax rates for casinos depending on their total revenue, the court said. The court gave the legislature four months to find a solution.

Mount Airy, in particular, portended the breakdown of relations between the two branches of government.

Soon after the rulings came down, Drew Crompton, chief legal counsel to the Senate Republicans, said the “abnormal” assignments wouldn’t necessarily be completed.

And while Crompton said at the time that he appreciated the deference given by the court to allow the legislature to find a remedy to the unconstitutional statutes, the timing of the opinions and the deadlines did raise at least one question about a court still coming into its own.

“What strikes me as odd is we got two back-to-back,” Crompton said. “Is this going to be a pattern?”

Two weeks before the legislature’s deadline in Mount Airy was set to expire in January 2017, lawmakers petitioned the court for more time. The justices obliged, extending the deadline to May 2017, but Wecht, who had penned the majority opinion in Mount Airy, issued a scathing dissenting statement, arguing that “the General Assembly had ample opportunity to amend the act; it simply lacked the political will to do so.”

“Although extending our stay here is nonprecedential in theory, the message sent to the General Assembly—that the decisions this court issues can be negotiated post hoc—doubtless will endure,” Wecht said. “Having granted the senators’ application for relief, in other words, these sorts of requests likely will become the rule rather than the exception.”

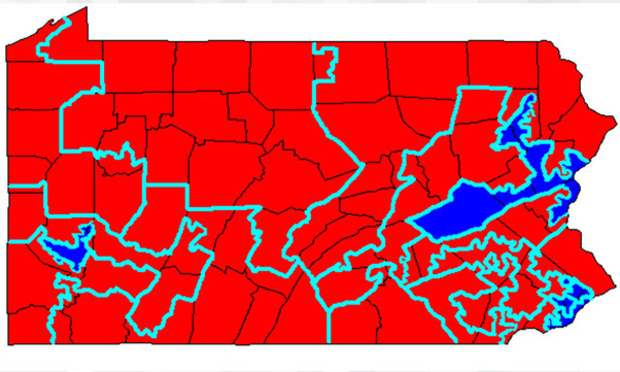

And so it was against that backdrop that the court issued its Jan. 22 ruling in League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The majority, led by Todd, invalidated the Congressional Redistricting Act of 2011 as unconstitutional and gave the legislature and the governor until Feb. 15 to come up with a new districting plan, warning that if they failed to do so the court would take matters into its own hands to “proceed expeditiously to adopt a plan based on the evidentiary record developed in the Commonwealth Court.”

Todd, Wecht, Donohue, Dougherty and Baer were all in agreement that the current congressional map is unconstitutional. Mundy and Saylor dissented in full.

Baer, however, also issued a concurring and dissenting statement to argue against rushing to redraw the map ahead of the May primary.

“It is naïve to think that disruption will not occur,” Baer said. “Prospective candidates, incumbents and challengers alike, have been running for months, organizing, fundraising, seeking their party’s endorsements, determining who should be on canvassing and telephone lists, as well as undertaking the innumerable other tasks implicit in any campaign—all with a precise understanding of the districts within which they are to run, which have been in place since 2011. … This says nothing of the average voter, who thought he knew his congressperson and district, and now finds that all has changed within days of the circulation of nomination petitions.”

The decision ultimately did fall to the Supreme Court, which issued a new congressional map Monday. In its per curiam decision, the court said the map “draws heavily upon the submissions provided by the parties, intervenors, and amici.” The decision again drew dissents from Saylor, Mundy and Baer.

Some observers said they share Baer’s concerns that adopting a new map so close to the next primary will only exacerbate an already fraught situation.

Castille said he believed the deadline the court imposed on the legislature and governor was too tight, and put the court in the “sticky” situation of playing a role in crafting the map. He said that when redistricting state districts came before the Supreme Court in 2012, the court gave the legislature much more time.

“We always gave them time and tried to give them an idea of what to do,” Castille said. “Instead the court just said, ‘You do it.’ I don’t know what kind of guidance that is for pretty serious stuff.”

“They overstepped their, maybe not authority, but ability to get this thing done in a measured way,” Castille added.

Overall, Castille, who is a Republican, said he agreed with Baer’s approach.

But others said they felt the court acted properly, or at least understandably, given the significance of the issue and what some viewed as the legislature’s history of inaction.

“The case really deserved fast action. This type of gerrymandering is a threat to democracy, and I think that the court’s are right to deal with these issues expeditiously,” said Robert L. Byer, chair of the appellate division of Duane Morris’ trial practice group.

Cooper said the legislature is used to getting its way, and giving the legislature more time would not have solved the issue.

“The legislature wouldn’t do anything in two years. They’d still come up against the deadline,” he said.

The attorney who said the legislature seemed to be working to bully the court added that the justices may have decided to impose a tight deadline after witnessing the General Assembly’s lax response to previous attempts to give lawmakers more time.

“I think after what they saw in Mount Airy, the court said, ‘If we don’t put some parameters on there,’” the legislature won’t do anything, the attorney said.

Several court and political watchers acknowledged that a battle between the court and the legislature over an issue as politically charged as redistricting was always going to be ugly.

“No matter what they did this was going to be seen in a political light,” Jeff Jubelirer, vice president of Bellevue Communications Group and a political observer, said of the court.

But given how strained relations between the two branches were even before the redistricting fight, many predicted the current row would have far-reaching ramifications.

“I think that this has caused a breach in how the court and the General Assembly are going to interact each with other” going forward, said the attorney who characterized the branches’ current relationship as “open war.”

Meanwhile, Castille, Jubelirer and others said it’s possible the legislature could retaliate by slashing the court’s budget.

And with the court now cast as the self-made arbiter of an extremely contentious political issue, the situation is not likely to improve any time soon.

“No one in the world could create a map where everyone says this is a good thing,” Jubelirer said, adding, ”This could further politicize Pennsylvanians’ views of our courts.”

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

Pennsylvania’s previous congressional map, which the state Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional Jan. 22. Photo courtesy of state of Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania’s previous congressional map, which the state Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional Jan. 22. Photo courtesy of state of Pennsylvania.