Emojis taken from Surveying the Law of Emojis paper, published by Eric Goldman, Santa Clara University – School of Law.

Emojis taken from Surveying the Law of Emojis paper, published by Eric Goldman, Santa Clara University – School of Law.

How will the courts deal with questions of interpretation raised by emojis?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

A survey of cases by Santa Clara University School of Law professor Eric Goldman found 80 opinions through 2016 that contained the term “emoticon” or “emoji,” with about half of those cases occurring the past two years. Goldman posted his findings on SSRN on Monday in a paper that encourages courts and practitioners “to prepare for the coming emoji onslaught.”

“I read a lot of cases and every now and then I see something new that I haven’t seen before, and it gets me thinking,” said Goldman in a phone conversation Thursday.

- Related: Am Law 100 Emoji Edition

In this case, it was an opinion that actually contained an emoji that sparked his curiosity and made him realize that in the text-based world of legal research there was no sure-fire way to find other opinions that included emoji.

Based on his research, Goldman expects a surge in legal disputes based on competing interpretations of emoji-based communications and fights over the intellectual property that underlies the small, digital pictographs themselves.

“Everyone is using emojis and many people don’t understand the technological underpinnings and the potential legal consequences” of emoji-based miscommunication, Goldman said.

Here three takeaways from Goldman’s findings.

All Emoji Aren’t Created Equal

That cow emoji you’re texting might not be the same as the cow the receiver sees on the other end of that text message.

Although a cow is one of the roughly 2,000 emoji defined by the Unicode Consortium, which sets software internationalization standards, Google, Microsoft, Apple and other tech companies have veered significantly from Unicode’s black-and-white line drawing of cow. Some have adopted the black-and-white spots associated with dairy cows, others the brown fur associated with beef cows. Others have gone with more cartoon-style images and included accessories such as a cow bells. What cow appears on any given screen—or if a cow appears at all—depends on the implementation of the emoji on either end of the communication.

Although variations in images of cattle in text messages might not provide obvious fodder for a legal dispute, Goldman points one example that seemingly could be.

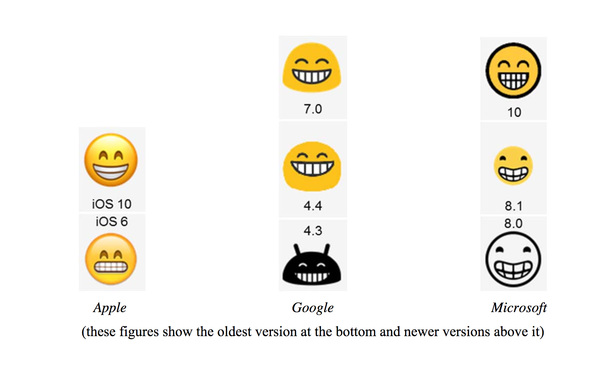

The “Grinning Face With Smiling Eyes” emoji changed significantly between different versions of Apple’s iOS operating system. For iOS 6.0 users the emoji shows a face with clenched teeth in a straight mouth while for iOS 10.0 it shows a wide, curved grin. One study showed that people interpreted the earlier implementation to mean “ready to fight” while the later version is more clearly smiling and happy. Someone on a new iPhone sending that emoji to someone using an older version of iOS could unintentionally appear threatening.

Speaking by phone Thursday, Goldman said that he can foresee scenarios where both parties have legitimate, divergent understandings of a particular communication. “It strikes me as raising a bunch of uncomfortable legal problems,” Goldman said. “In the criminal context—someone could literally go to jail for thinking they were saying one thing when they were saying another.”

Get Ready for Emoji Trolls

Goldman suspects intellectual property law could be behind technology companies’ widespread practice of implementing their own versions of emoji. His hypothesis is that companies are creating their own emoji either to preserve their own trademark or copyright interests or to shield themselves from potential liabilities from others. “If this hypothesis is true, then IP law is causing the proliferation of unnecessary differences in emoji implementations that reduce IP risk but increase potential user confusion/misunderstanding,” he wrote.

Goldman said Thursday he expects the IP scrutiny of emoji to increase after the release of “The Emoji Movie” this summer, an animated film feature emoji as characters. He also said he would expect that some trademark and copyright holders will get aggressive in seeking licensing fees from emoji platforms. “Trolling behavior shows up in a wide range of intellectual property. I don’t see why it won’t occur here as well,” he said.

Courts Catching Up

Goldman’s study identified how the text-based legal research tools fail to capture visual communications in opinions. In a footnote high in the paper, he notes that the paper is best read in PDF form since electronic databases aren’t likely to include most images and are unlikely to warn of the graphical omissions.

Lexis and Westlaw aren’t alone in their struggle dealing with emojis. The courts, likewise, are figuring things out on the fly. In the criminal trial against the operator of the Silk Road online black market, federal prosecutors reading text messages to jurors initially skipped over any references to emoji. U.S. District Judge Katherine Forrest in the Southern District of New York, however, eventually required prosecutors to orally describe the emojis as they read.

Goldman said Thursday that judges are one of his target audiences for the paper. Said Goldman, “Questions are being asked about emojis and there aren’t that many answers.”

:-/

Ross Todd is bureau chief of The Recorder in San Francisco. He writes about litigation in the Bay Area and around California. Contact Ross at [email protected]. On Twitter: @Ross_Todd