Much has been written about why the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent 5-4 decision in Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, __ S. Ct. __, 2018 U.S. LEXIS 3086, was a victory for arbitration in yet another battle in the war between management and labor. Given the court’s recent pro-arbitration jurisprudence, the decision might be seen as inevitable—at least until Congress steps in to provide greater regulation of consumer or employee arbitrations as it did in Dodd-Frank for a limited number of financial transactions. We suggest a different take on the case, one that does not bode well for even-handed decision making by an aggressive Supreme Court conservative majority.

First, though, some background. In 2012, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that the 1935 National Labor Relations Act protected employees generally—not only those subject to collective bargaining agreements negotiated between a union and management—from being required to agree to waivers of the right to pursue federal statutory and other claims in a class action. Typically, these waivers were contained within a clause also mandating that all disputes be resolved through arbitration and not through the courts. The board held that the right of “concerted activities for the purpose of … mutual aid or protection” under section 7 of the NLRA overrode the mandates of the 1925 Federal Arbitration Act, section 2 of which declared arbitration agreements “valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save on such grounds as exist at law or equity for the revocation of any contract.” According to the NLRB, this “savings clause” meant that an employee could bring a class action to prosecute alleged violations of overtime, minimum wage and other federal labor laws despite a class-action waiver in an arbitration clause in their employment contract, pointing to the right of concerted action in section 7 of the NLRA as a defense to enforcement of the class-action waiver.

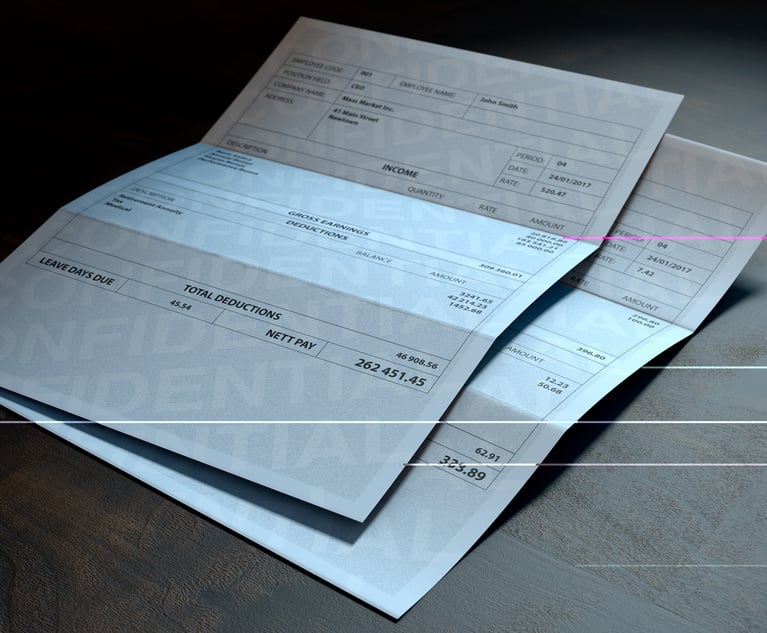

U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. – Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. – Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM