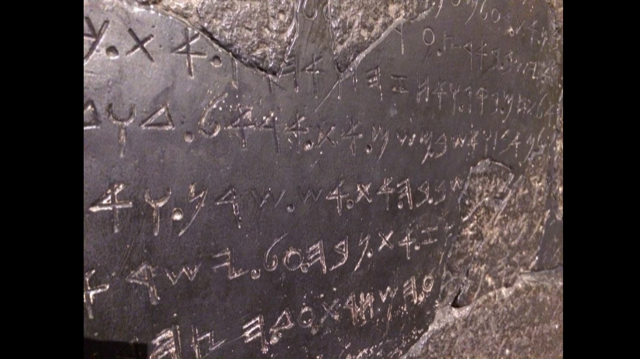

Wandering the basement of the Louvre in Paris, I was awed by a polished stone, an eight-foot-high, shining large basalt stele, edged with tiny cuneiform markings, surrounded by a small velvet rope. One of the oldest legal codes stood before me, I had to understand it, touch it. I sat on the floor for an hour, reading the museum-provided translation, of one of the first workers’ compensation codes ever written.

Etched in stone, immovable and unchanging, the Babylonian code of Hammurabi (1780 B.C.E.) lasted nearly a millennium.

Hammurabi’s Code. Photo courtesy of Jay H. Bernstein.

Hammurabi’s Code. Photo courtesy of Jay H. Bernstein.