Fraud has a tendency to ooze across borders, and fraudsters often locate in the jurisdiction of greatest laxity. This sets up an inevitable tension between prosecutorial zeal and legal doctrine. As most practitioners well know, U.S. law mandates a strong presumption against the extraterritorial application of a U.S. statute to foreign conduct. Since Morrison v. Nat’l Australia Bank, Ltd., 561 U.S. 247 (2010), this has been the law, and it has been enforced fairly strictly in cases involving private litigation. But once we move to the public enforcement arena, outcomes become less predictable.

Let’s start with the following facts, which are borrowed from the leading recent Second Circuit case on Morrison: A Chilean resident and citizen sues his cousin, who is also a resident and citizen of Chile, for misappropriation of his inheritance, which the cousin was supposed to protect as a fiduciary to the plaintiff/relative. The only real contact with New York was that the plaintiff’s funds were misappropriated from his New York bank account. Does Morrison preclude such a suit?

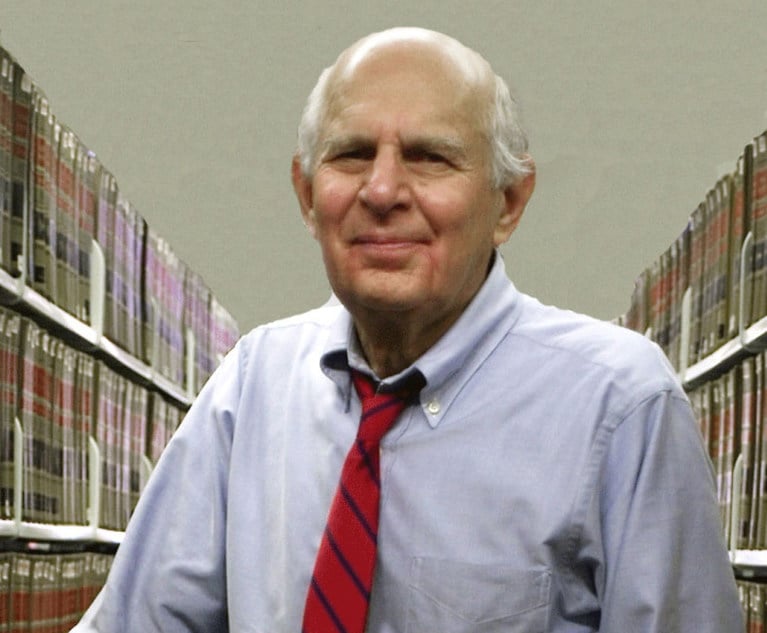

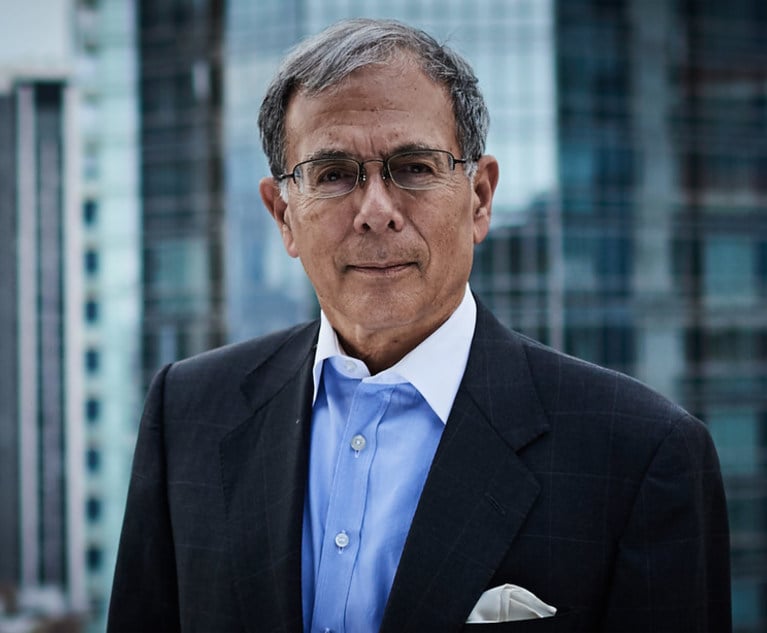

Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of FTX Cryptocurrency Derivatives Exchange, departs from court in New York, US, on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bankman-Fried was released on a $250 million bail package after making his first US court appearance to face fraud charges over the collapse of FTX, the cryptocurrency exchange he co-founded. Photo: Stephanie Keith/Bloomberg

Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of FTX Cryptocurrency Derivatives Exchange, departs from court in New York, US, on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bankman-Fried was released on a $250 million bail package after making his first US court appearance to face fraud charges over the collapse of FTX, the cryptocurrency exchange he co-founded. Photo: Stephanie Keith/Bloomberg