The article “New Statute Eliminating Waiver of Standing Defense Imperils Title Insurance (and Foreclosures)” (April 28) dispenses dire warnings about the parade of horribles that supposedly will ensue from a new law that makes the defense of lack of standing nonwaivable in a residential foreclosure action. Does newly enacted section 1302-a of the Real Property Actions and Proceedings Law (RPAPL 1302-a) truly give cause for alarm, though? Perhaps, but only for a foreclosure plaintiff who cannot show that it actually has the right to enforce the subject mortgage, and therefore the right to take the home that secures the mortgage loan. The Legislature is entirely justified in making clear that the courts can only adjudicate a foreclosure action when the party bringing the action has a stake in the matter.

The article reveals the author’s misunderstanding of the jurisprudential foundations of standing when he conflates standing with capacity to sue—a defense that, as he notes, the CPLR deems waivable. The Court of Appeals, however, draws a distinction between the two, and—in contrast to the capacity defense—nowhere does the CPLR include standing as one of the defenses which is waived if not timely asserted. While capacity “concerns a litigant’s power to appear and bring its grievance before the court,” standing “is an element of the larger question of justiciability” concerned with whether “the party seeking relief has a sufficiently cognizable stake in the outcome so as to cast the dispute in a form traditionally capable of judicial resolution.” Community Bd. 7 v. Schaffer, 84 N.Y.2d 148, 154-55 (1994) (citations, internal punctuation, and alterations omitted). If, through such a fundamental defect as the plaintiff’s lack of interest in the case, the matter cannot be judicially resolved, the court must be made aware of that impediment, no matter if the defendant failed to identify the problem at the case’s outset. RPAPL 1302-a merely codifies long-held judicial doctrine.

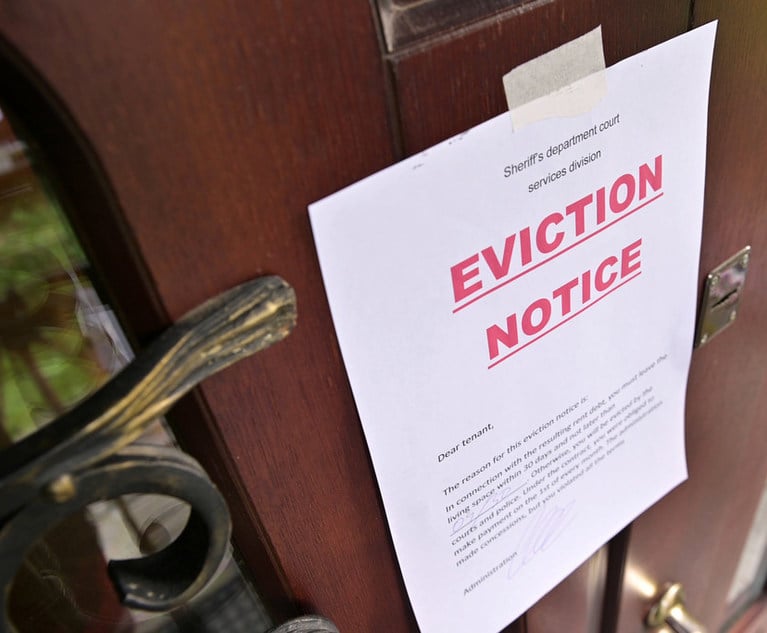

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock