In her withering dissent from the Supreme Court’s holding in Lamps Plus Inc. v Varela, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg began her opinion by underscoring “how treacherously the court has strayed” in this decision. And the damage to contract principles is greater than the treachery to the goals of the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). Even more fundamentally than the fact that, as Justice Ginsburg noted, the FAA was enacted “to enable merchants of roughly equal bargaining power to enter into binding agreements to arbitrate commercial disputes,” the FAA was intended to make sure state law does discriminate against or disfavor arbitration agreements, as Justice Elena Kagan articulated in her dissenting opinion. The court disregarded this by sidelining the general contract law principle of contra proferentem—construing an ambiguity against the drafter—which does not disfavor arbitration afoul of the FAA, to favor a view of arbitration that discriminates against its class-wide pursuit. In doing so, the court further undermines the project of differentiating between types of contracts and muddies the doctrinal distinctions and rationales that underpin this important project.

In reaching its decision, the Supreme Court continued its worrying trend of expanding the reach of arbitration provisions to preclude consumers and employees from holding companies accountable for negligence and other harms through the law. It also upended basic principles in contract law—not least the meaning of consent. The court’s majority ruled that an ambiguously drafted employment agreement barred workers from class-wide arbitration of a claim against their employer for compromising their personal data. As a result, each employee must arbitrate his or her claim individually against the company after it disclosed workers’ tax information in a phishing scam.

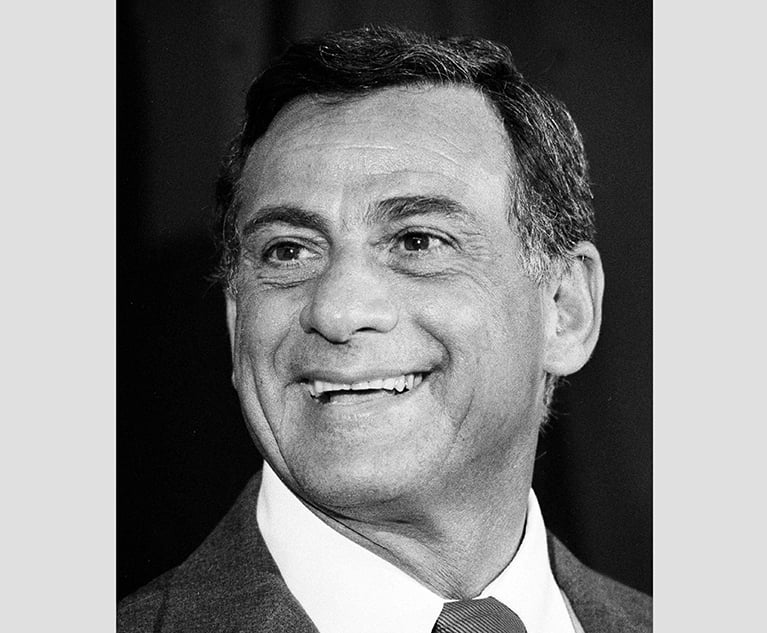

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg speaks at New York Law School on Feb. 6. Photo: Carmen Natale/ALM.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg speaks at New York Law School on Feb. 6. Photo: Carmen Natale/ALM.