Consumer Financial Protection Bureau building in Washington, D.C., June 4, 2013. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau building in Washington, D.C., June 4, 2013. Photo by Diego M. Radzinschi/THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

A federal appeals court on Wednesday upheld the lawfulness of the single-director power structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Obama-era agency undergoing a dramatic shift in focus as Trump-appointed officials take over leadership slots.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, sitting as a full court, said the president can only remove the director of the agency for cause, not at will. The mortgage company PHH Corp., represented by Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, had argued the leadership scheme lacked accountability.

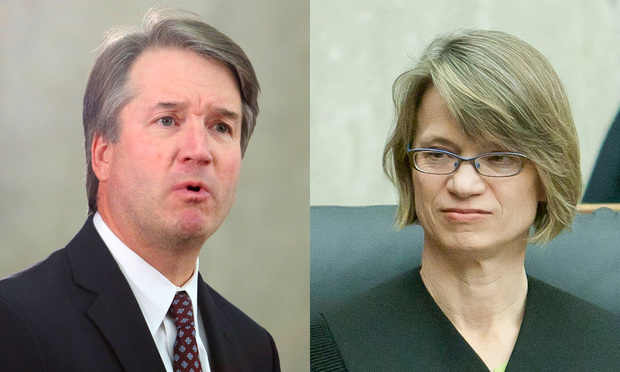

“Applying binding Supreme Court precedent, we see no constitutional defect in the statute preventing the president from firing the CFPB director without cause. We thus uphold Congress’s choice,” Judge Nina Pillard wrote for the court. Pillard also said: ”Congress’s decision to provide the CFPB Director a degree of insulation reflects its permissible judgment that civil regulation of consumer financial protection should be kept one step removed from political winds and presidential will. We have no warrant here to invalidate such a time-tested course.”

PHH didn’t walk away empty-handed. The company still has a chance to challenge anew the $109 million penalty the agency imposed for alleged misconduct. Wednesday’s decision in part reversed an October 2016 ruling by a divided three-judge panel of the D.C. Circuit, which struck down the agency’s structure but said the penalty should be revisited. The full D.C. Circuit on Wednesday left intact the panel’s ruling that the CFPB had misinterpreted the law at issue in its case against PHH—the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act.

Judge Brett Kavanaugh, who wrote the 2016 opinion, argued again Wednesday—this time in dissent—that independent agencies should be run by multimember commissions, a design akin to agencies such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and Federal Trade Commission.

U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit Judges Brett Kavanaugh and Nina Pillard. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit Judges Brett Kavanaugh and Nina Pillard. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

“The independent agencies collectively constitute, in effect, a headless fourth branch of the U.S. government. They hold enormous power over the economic and social life of the United States,” Kavanaugh wrote. “Because of their massive power and the absence of presidential supervision and direction, independent agencies pose a significant threat to individual liberty and to the constitutional system of separation of powers and checks and balances.”

The ruling Wednesday isn’t expected to present significant consequences in the short term. President Donald Trump installed White House budget director Mick Mulvaney as the CFPB’s interim leader after Thanksgiving, replacing Richard Cordray, the Obama-appointed director who’s now running for Ohio governor. Trump has not yet nominated a permanent replacement for Cordray.

The D.C. Circuit’s decision would come into play if the winner of the next presidential election tries to replace Trump’s director, a position that carries a five-year term. Cordray’s term was set to end next July. After Trump’s win, there was debate in legal circles and on Capitol Hill over whether the president would—or even could—fire Cordray outright and replace him with his own nominee.

Still, Wednesday’s ruling renewed attention on an agency in the spotlight for weeks now. The decision comes as an unrelated legal fight—focused on the acting director of the agency—plays out in the D.C. Circuit.

Lawyers for the consumer bureau’s deputy director, Leandra English, are fighting in the D.C. Circuit to overturn a judge who twice now has upheld Mulvaney’s role as interim director of the agency. English’s lawyers argue Mulvaney’s appointment violated the procedure set out in the Dodd-Frank financial reform law, which created the CFPB. They contend English, as deputy director, was next in line to temporarily lead the bureau.

Ted Olson of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher

Ted Olson of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher

A lawyer for PHH, Gibson Dunn partner Theodore Olson, was not immediately reached for comment about Wednesday’s ruling.

Critics of the CFPB’s structure had argued the White House should have the power to fire the CFPB director at will, not just for cause. A three-judge panel of the D.C. Circuit in October 2016 found the single-director structure too untethered from White House supervision to be lawful.

In that ruling, Kavanaugh called the director one of the most powerful positions in the capital.

The agency is sure to undergo changes in the next several months, and for the remainder of the Trump presidency. New leadership has already begun to shift priorities. Republican leaders on Capitol Hill thwarted Cordray’s signature push to boost the power of consumers to sue banks in court.

Mulvaney has said his team is reviewing the CFPB’s cases, and already the agency suspended one investigation and dropped another. The CFPB in its six-year existence has collected billions of dollars in penalties from mortgage companies, lenders and debt collectors. The Wall Street Journal has reported that companies have spent billions of dollars in compliance costs.

Wednesday’s decision in the D.C. Circuit was largely expected. The appeals court at a hearing in May didn’t appear inclined to strike down the CFPB’s structure as unconstitutional.

Olson of Gibson Dunn had urged the court to dismiss a $109 million penalty that the agency imposed for orchestrating an alleged kickback scheme. Many companies in the financial sector pointed to PHH’s case in urging judges around the country to strike a blow against the consumer bureau.

Cordray, amid the tumult over his agency, tried to remained cool and tried, behind the scenes, to lift spirits at times. After the D.C. Circuit panel in October 2016 ruled against the lawfulness of the single-director structure, he sent CFPB staff the lyrics to one of his favorite Bob Dylan songs, “Forever Young.”

“Nothing about this ruling will be final in the interim,” Cordray wrote in a letter then. “Second, even if this outcome were to stand, which it may or may not, the court went out of its way to state, explicitly, that its proposed remedy on the constitutional claim ‘will not affect the ongoing operations of the CFPB.’”

Cordray wrote that memo to staff before Trump won the White House.

The Supreme Court’s probably the next venue, but it’ll get tricky there.

The U.S. Justice Department, under Attorney General Jeff Sessions, abandoned its defense of the CFPB back in March 2017. Still, the CFPB—with Cordray still at the helm—was able to defend itself in the D.C. Circuit, sending appellate lawyer Lawrence DeMille-Wagman to argue for the bureau in May.

The CFPB’s authority to mount a self-defense ended there. Under the Dodd-Frank Act, which created the agency, the CFPB enjoys independent litigating up through the circuit court but needs the Justice Department’s permission to argue before the Supreme Court.

If PHH takes the case to the high court, it’s unclear who will defend the D.C. Circuit ruling. The Justice Department, in the Supreme Court, would argue against the constitutionality of the independent single-director power scheme.

When asked Wednesday about whether the CFPB would make a written request to represent itself before the Supreme Court, a spokesman said only that the agency was “analyzing the decision.”

In cases where no party is defending a lower-court ruling, the justices have the option to appoint a lawyer to do just that. The Supreme Court this month appointed an O’Melveny & Myers partner to defend a D.C. Circuit ruling upholding the constitutionality of the SEC’s administrative law judges. That case will be argued later this term. In that case, the Justice Department also reversed its earlier litigation stance.

The consequences of the D.C. Circuit decision will touch many pending cases.

The D.C. Circuit decision—unless or until it’s overturned—effectively forecloses one avenue of attack companies mounted against the agency in many federal cases across the country.

Companies in the CFPB’s crosshairs seized on the October 2016 panel ruling that struck down the agency’s structure as unconstitutional. Lawyers for financial services companies pointed to the decision to bolster their argument that the CFPB’s enforcement action against them—whether a lawsuit or an investigation—was unlawful because so too was the agency’s structure.

In Florida, a mortgage servicing company took the piggybacking even further. Ocwen Financial Corp.—represented by Greenberg Traurig and Goodwin Procter—invited the Justice Department to tell the court that the the government was no longer backing the independence of the agency. The Justice Department ultimately decided not to take Ocwen up on the offer to weigh in.

The decision will most immediately be felt in Washington federal district court, which is bound by D.C. Circuit precedent. Shortly after the en banc D.C. Circuit handed down its decision Wednesday, a federal district judge ordered the CFPB and a company challenging an agency investigation to state their positions “concerning the effect, if any,” of the PHH Corp. ruling.

Don’t forget about RESPA. Companies will look anew at how the CFPB reinterprets this law.

For the CFPB’s challenger, PHH, Wednesday’s ruling was not a complete loss. And that part of the decision—concerning the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act—could benefit companies facing CFPB investigations. The D.C. Circuit left intact the panel’s decision that the CFPB had misinterpreted the law at issue in the underlying enforcement action: the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act.

Cordray ordered PHH in 2015 to pay $109 million after finding that the mortgage company had unlawfully referred consumers to insurers in exchange for kickbacks. In 2016, the law firm Mayer Brown described Oct. 11—the date of the D.C. Circuit panel decision striking down that penalty—as a “banner day” for real estate brokers, agents, lenders and title companies subject to the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act.

With Wednesday’s decision, it is likely that the CFPB will sharply reduce the $109 million in ordered disgorgement or drop the case entirely.

“The combination of that opinion and Acting Director Mulvaney’s recent statement that the bureau would stop “pushing the envelope” on enforcement matters will provide PHH with strong arguments for why the case should be dropped,” said Eric Mogilnicki, a partner at Covington & Burling.