Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJ

Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / NLJ

Whether lawyer or justice, if you’re going to take on Ruth Bader Ginsburg on a jurisdiction issue, be advised. Justice Neil Gorsuch tried in a decision Monday and lost. As a parting shot, he chided a majority that, he said, was losing sight of “a federal government of limited and enumerated powers.”

The Ginsburg majority and Gorsuch dissent in Artis v. District of Columbia offered a snapshot of the high court’s resident jurisdiction expert going toe-to-toe with the court’s junior justice, whose textual and often didactic approach to judging continue to shed light on the kind of justice he is.

Ginsburg’s reputation in the field of jurisdiction and civil procedure is well-established. As Justice Elena Kagan noted in a 2014 appearance at the New York City Bar Association: “As a law professor, [Ginsburg] was a pathmarking scholar of civil procedure.”

Scott Dodson of the University of California Hastings College of Law in his article, “A Revolution in Jurisdiction, in The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” wrote that as a justice “Ginsburg has had an enormous impact—perhaps even rivaling her impact in gender equality—on the law of civil procedure and federal jurisdiction. Perhaps more so than any other justice, Ginsburg has had a special solicitude for the topic throughout her career.”

Of course, that doesn’t mean the justice is infallible on jurisdiction questions but advocates know that if there is a jurisdictional weakness in their cases, Ginsburg will find it and they must be well-prepared to answer her questions.

In Monday’s decision, Ginsburg was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. and Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan. The case raised the kind of issue that the Roberts Court seems to relish even if it might put the casual observer to sleep: How long does a tolling provision in the federal supplemental jurisdiction statute give someone to refile certain claims in state court after a federal court has dismissed them and before the state statute of limitations kicks in?

Ginsburg said the ordinary meaning of “tolled” is to stop the clock. The statute of limitations is suspended while the claims are pending in federal court and for 30 days afterwards. That interpretation, she said, is a “natural fit” with the language of the federal supplemental jurisdiction statute.

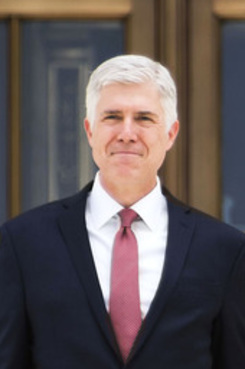

Justice Neil Gorsuch. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi

Justice Neil Gorsuch. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi

Gorsuch, in a dissent joined by Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito Jr., accused the majority of abandoning the traditional rule “grown from a rich common law and state statutory tradition” in favor of a new federal rule. The traditional rule, he said, was a 30-day grace period after the claims were dismissed.

Gorsuch offered a list of “absurdities” that would follow Ginsburg’s interpretation. To which, Ginsburg replied in a footnote: “The dissent conjures up absurdities not presented by this case.” She continued: “Should the extraordinary circumstances the dissent envisions in fact exist in a given case, the comparison the dissent makes would be far from inevitable.”

Gorsuch said the common-law rule known as the “journey’s account” supported his interpretation of a 30-day grace period. Responding to what Ginsburg called Gorsuch’s “history lesson on the ancient common-law principle of ‘journey’s account,’” she said: “Nothing suggests that the 101st Congress had any such ancient law in mind when it drafted [the tolling provision]. More likely, Congress was mindful that ‘suspension’ during the pendency of other litigation is ‘the common-law rule.’”

Gorsuch countered, also in a footnote: “The court dismisses this ‘history lesson’ on the ground that it doesn’t know if Congress had ‘the ancient common-law … in mind.’ But respect for Congress’s competency means we presume it knows the substance of the state laws it expressly incorporates into its statutes and the common law against which it operates.”

In the end, Gorsuch’s textual interpretation and his federalism concerns did not overcome the majority’s views. He ended his dissent with this final dig at the majority:

“The court today clears away a fence that once marked a basic boundary between federal and state power. Maybe it wasn’t the most vital fence and maybe we’ve just simply forgotten why this particular fence was built in the first place. But maybe, too, we’ve forgotten because we’ve wandered so far from the idea of a federal government of limited and enumerated powers that we’ve begun to lose sight of what it looked like in the first place.”

Ginsburg did not leave Gorsuch’s federalism shot unaddressed. Under Gorsuch’s interpretation, she said, plaintiffs simply could file two lawsuits, instead of one, and ask the state court to hold the suit filed there in abeyance until the federal suit was decided. “How it genuinely advances federalism concerns to drive plaintiffs to resort to wasteful, inefficient duplication to preserve their state-law claims is far from apparent.”

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Artis v. District of Columbia is posted below.