“A response having been filed, the Order to Show Cause, dated December 8, 2014, is discharged. All Members of the Bar are reminded, however, that they are responsible—as Officers of the Court—for compliance with the requirement of Supreme Court Rule 14.3 that petitions for certiorari be stated ‘in plain terms,’ and may not delegate that responsibility to the client.”

Linda Yun, a spokesperson for Foley & Lardner, said: “We are pleased with and respect the Court’s decision regarding this highly unusual matter.” Shipley declined to comment.

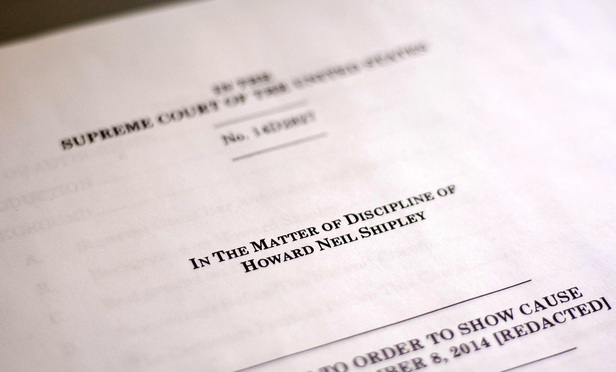

Last Dec. 8, the court issued an order directing Shipley “to show cause, within 40 days, why he should not be sanctioned for his conduct as a member of the Bar of this Court in connection with the petition for a writ of certiorari in No. 14-424, Sigram Schindler Beteiligungsgesellschaft MBH v. Lee.”

The court at the time did not say why it was upset with his petition in the patent case, but its content revealed the likely reason: it is filled with obscure acronyms, convoluted sentences and technical lingo. It also contained a footnote that may have raised eyebrows at the court: “Prof. Sigram Schindler, the primary inventor of the ’453 patent, should be recognized for significant contributions to this petition.” Schindler, the client in the case, is a computer-sciences professor at the Technical University of Berlin and head of a technology company.

Shipley got an extension until Feb. 19 to respond. During that period, the court reassessed its long-standing policy of keeping disciplinary cases confidential and said that beginning Feb. 1, responses to show-cause orders would be public. That meant Shipley’s defense would not be confidential.

Shipley hired former U.S. Solicitor General Paul Clement, now with Bancroft, to write his response. Clement acknowledged the brief was “unorthodox” and said, “The final product was certainly not what Mr. Shipley would have filed if he were representing a more deferential client.” But Schindler “insisted on retaining primary control over the substance of the petition,” Clement said.

Torn by “the competing demands of the loyalty that he owed his client and the duty he owed [the court] as a member of the Supreme Court bar,” Clement wrote, Shipley decided to file the brief the way the client wanted it to read. Clement also noted that several similar briefs had been filed on Schindler’s behalf in past cases without complaint from the court.

The high court from time to time disbars lawyers from the Supreme Court bar in response to similar sanctions meted out by other courts. Shipley’s case is the first since 2000 when the court threatened to punish a lawyer for actions taken before the Supreme Court itself.

Update: This post was updated with comment from Foley & Lardner.

Read more: