The U.S. Supreme Court returns from a mid-winter break to an argument docket jam-packed with same-sex marriage, voting rights, DNA testing, gene patenting, class actions, Indian adoptions and other issues.

Many of the cases to be argued in the next three sessions have the potential to divide the justices narrowly and some, bitterly. To paraphrase Bette Davis in the classic movie, "All About Eve," fasten your seatbelts; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

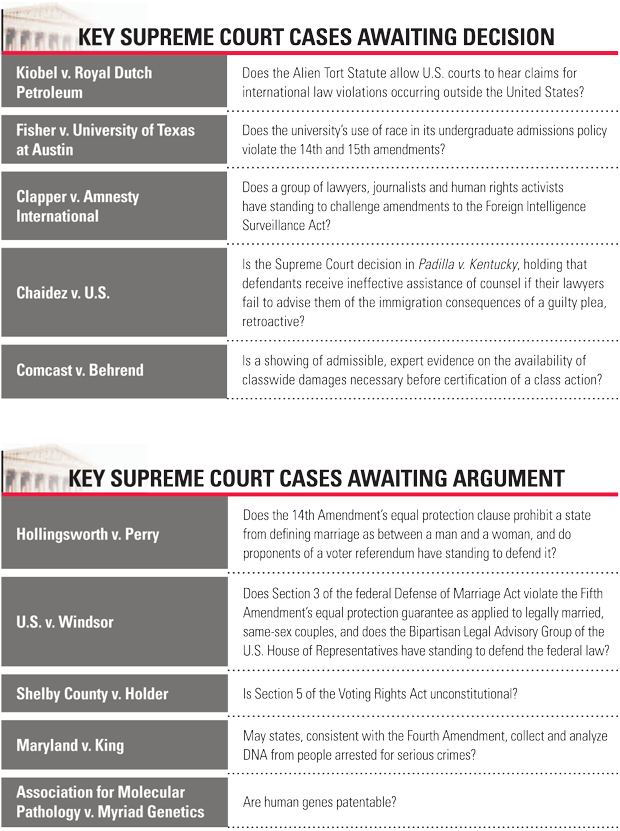

Besides those cases waiting to be heard, there are major ones waiting to be decided. Two were argued last October and one of the two was the first argument of the term.

The oldest case pending decision is Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., argued on Oct. 1. That case is actually a re-argument from last term in which the justices expanded the question to be decided.

In Kiobel, a group of Nigerian nationals initially asked the justices whether corporations could be held liable under the Alien Tort Statute for violations of international law or treaties signed by the United States. However, after arguments last term, the Court ordered re-argument to address whether the more than 200-year-old statute allows U.S. courts to hear lawsuits for those violations committed on foreign soil.

The second October case that could be a blockbuster is Fisher v. University of Texas-Austin, a challenge to the university’s use of race as a factor in its undergraduate admissions policy. Nearly three dozen amicus briefs were filed in the case. When Fisher is combined with the term’s voting rights case and two same-sex marriage cases, the overall amicus outpouring is likely to reach historic proportions.

And, the combination of affirmative action, voting rights and same-sex marriage reinforces conventional wisdom that this term is likely to be as significant as last termthough in a very a different way.

"I do think equality is the dominant theme this term, exemplified by the affirmative action case, voting rights, and same-sex marriage, in the same way last year, looking at the two biggest casesthe Affordable Care Act and U.S. v. Arizonawere both essentially about federalism," said Associate Dean Vikram Amar of the University of California-Davis School of Law.

On the criminal law side of the docket, high-tech and low-tech challenges involving the Fourth Amendment await the justices.

Last November, the Court heard arguments in the sagas of Aldo and Franky, drug-sniffing police dogs in Florida v. Harris and Florida v. Jardines. The constitutionality of their low-tech noses may well depend on how much privacy the justices accord a pick-up truck’s door and the front door of a house.

On Feb. 26, the Court moves into the high-tech arena as it examines in Maryland v. King whether the Fourth Amendment allows states to collect and analyze DNA from persons who are arrested, but not yet convicted of violent crimes. Prosecutors, defense attorneys, civil liberties groups and genetic and forensic scientists have offered the justices their opinions on what the outcome should be.

Over the last five decades, the Court’s Fourth Amendment cases have evolved from concerns about race to the development of the exclusionary rule to concerns for public safety to the new technology and its Orwellian overtones, according to scholars in this area. In last term’s high-tech Fourth Amendment case involving law enforcement’s use of GPS tracking devices, some justices even mentioned Orwell’s "1984" during oral arguments.

The business cases being argued in the final three sessions of the term are being closely watched by the business community and consumers as they raise major and difficult issues in several areas for the justices to resolve.

"A great many of the cases on the business side of docket were déjà vu cases," said Catherine Stetson of Hogan Lovells, explaining, "There is a continuing theme about cases being picked up that follow directly and immediately from cases decided last term or the term before."

For example, the already-argued Comcast v. Behrend and Amgen Inc. v. Connecticut Retirement Plans involve issues surrounding certification of class actions, she said, follow-ups to Wal-Mart v. Dukes in 2011. Mutual Pharmaceutical Co. v. Bartlett, concerning preemption of state law design-defect claims targeting generic pharmaceutical products, flows from the 2011 ruling in Pliva v. Mensing. And the challenge to the patentability of human genes in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics has an antecedent in the 2012 decision in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Labs.

In addition to those cases, Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis asks the justices whether reverse payment agreements (also known as pay for delay) between brand name drug manufacturers and potential generic competitors are per se lawful or presumptively anti-competitive and unlawful.

"This is one of the hardest antitrust cases I’ve ever seen," said appellate and antitrust litigator Roy Englert Jr. of Robbins, Russell, Englert, Orseck, Untereiner & Sauber. "There are many layers of complexity. I believe the votes of seven justices are in play. I expect justices [Sonia] Sotomayor and [Elena] Kagan will vote for the FTC."

Despite the varied cases of the term, most eyes during these last few months will be on the voting rights and same-sex marriage cases.

The voting rights challenge, Shelby County v. Holder, will be heard on Feb. 27 and asks whether Congress exceeded its authority under the 14th and 15th amendments when it reauthorized Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act in 2006 under the pre-existing formula for determining which states and municipalities should by covered. Section 5 requires covered jurisdictions to get federal preclearance of any changes in voting practices.

And Hollingsworth v. Perry, involving California’s ban on same-sex marriages, and U.S. v. Windsor, a challenge to Section 3 of the federal Defense of Marriage Act, will be argued on March 26 and March 27, respectively. Section 3 defines marriage as between a man and a woman for all federal purposes.

"I do think they will reach the merits in the voting rights case. The Court can’t be happy that it gives Congress one last chance to do something, to clean up the legislative findings, and Congress doesn’t do anything in three years," said Amar referring to the justices’ 2009 decision in Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder. "If the Court is to be taken seriously, it’s got to back it up a little bit. Maybe they’ll strike [Section 5] down but provide a recipe for Congress to reenact a more narrow carefully crafted version."

But Amar and others are not at all certain that the justices will get to the merits of the same-sex marriage cases, both of which raise standing problems.

"What are they gaining if they defer the merits?" asked Amar. The same-sex marriage landscape is rapidly changing, he said, adding, "A few years could provide the Court with a lot more data than it has now. In 2014, I could imagine Proposition 8 invalidated and you could have a dozen more states adopt same-sex marriage. Going from 10 to 20 would be a huge difference for someone like Anthony Kennedy."

Marcia Coyle can be contacted at [email protected].