If you are trying to fix something, you need the right tool for the job. This basic principle is central to judging and especially important when judges are considering efforts to expand one of the most powerful constructs in the civil justice system: the class action. Over the past three years, the federal circuit courts and now the U.S. Supreme Court have weighed in on efforts to use class action lawsuits as a means to address the complex policy issue of forced labor in global supply chains. These courts have all reached the same conclusion: Class actions are not the right tool for the job.

This past term, the U.S. Supreme Court considered that issue in Nestle v. Doe, a long-running putative class action that posed the question of whether courts could read into the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) a cause of action against domestic corporations for labor abuses occurring on cocoa farms located in the Ivory Coast. The ATS does not authorize any claim against domestic corporations for this sort of extraterritorial activity. But several former workers on one of these farms nonetheless sued U.S.-based food companies in a putative class action asking the court to create a cause of action to hold these domestic corporations liable on an “aiding and abetting” theory.

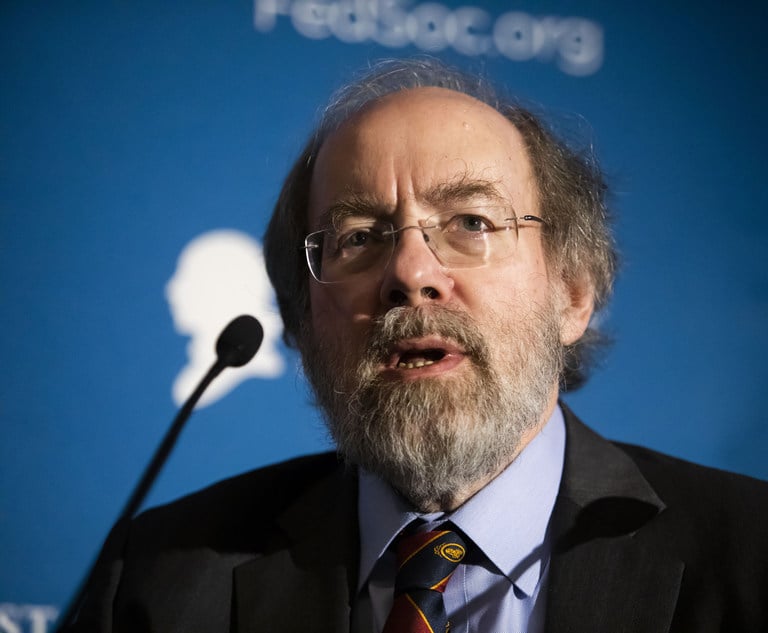

Charles C. Sipos, partner at Perkins Coie and co-chair of the firm’s food litigation industry group. Courtesy photo

Charles C. Sipos, partner at Perkins Coie and co-chair of the firm’s food litigation industry group. Courtesy photo