Former law clerks as well as the so-called “feeder” judges and law professors who fill the pipeline with potential clerks point to numerous factors that contribute to the dearth. Among them: intense competition to hire top law students at the appeals court level and the range of other opportunities that top minority law students have.

And yet, most justices appear to be taking a passive approach to diversity rather than actively seeking minority clerks or pushing their networks to identify more diverse candidates. “I’ve never had that precise conversation with any justice,” said Harvard Law School professor Richard Lazarus, a comment echoed by several other clerk-recommenders interviewed for this story. And note this about the feeder judges the justices seek clerks from: The top 19 feeder judges—whose former clerks make up more than two-thirds of all Supreme Court clerks—are white males, according to the NLJ’s research.

➤➤ SCOTUS Clerks: Who Gets the Golden Ticket? Join reporter Tony Mauro and Hogan Lovells partner Neal Katyal on Thursday, Dec. 14 for a conference call about clerk hiring and diversity. Click here for more details.

At a 2010 budget hearing, Justice Clarence Thomas seemed to confirm the court’s passivity when asked about minority hiring. “I don’t think it’s up to us to change other federal judges’ hiring practices.” He added, “The reality is that Hispanic and blacks do not show up in any great numbers” in the ranks of candidates recommended by the feeder judges.

Georgetown University Law Center professor Sheryll Cashin, a former Thurgood Marshall clerk, said the justices need to be more proactive. “If diversity were a priority,” said Cashin, who’s African-American and expert on civil rights issues, “it would not be hard to find qualified people of color even in the elite universe that some of the justices are used to.”

In fact, two of the justices—Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer—have hired roughly equal numbers of men and women—suggesting a proactive approach pays off.

As with the 1998 survey, the NLJ research on clerks was accomplished through scrutiny of available public information, as well as phone calls and emails directed at former clerks and others—not all of whom responded. Unlike other tribunals, including lower federal courts, the Supreme Court does not maintain or release any demographic data about clerks, according to spokeswoman Kathy Arberg.

The National Law Journal asked all nine justices to help verify our data, and all nine declined, Arberg said. All nine justices also declined to be interviewed about the diversity issue generally.

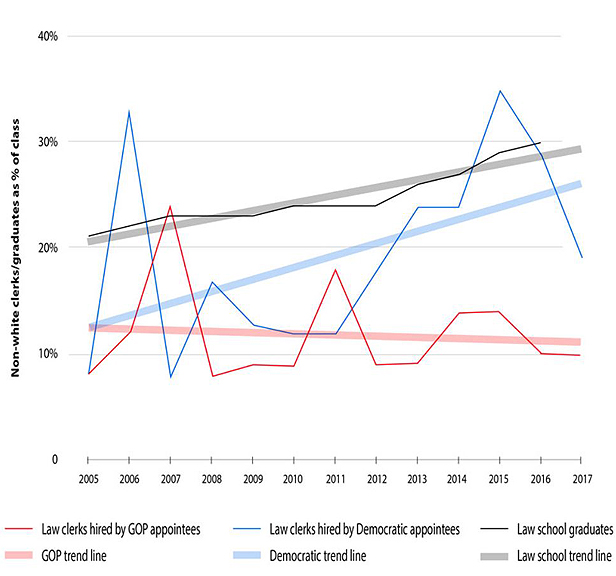

Among the NLJ’s key findings:

• Since Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. joined the court in 2005, just 8 percent of the law clerks he’s hired have been racial or ethnic minorities.

• At the other end of the spectrum, more than 30 percent of Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s clerks have been non-white, making her chambers the most diverse among those justices who have been on the court for more than a year. (Justice Neil Gorsuch has hired seven clerks so far over two terms, three of whom are non-white, for a total of 43 percent.)

• Low numbers span the court’s ideological spectrum. Only 12 percent of the clerks hired by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Clarence Thomas since 2005 were minorities. Ginsburg has hired only one African-American clerk since she joined the high court in 1993, and the same goes for Justice Samuel Alito Jr., who became a justice in 2006.

• While Ginsburg and Breyer have hired men and women in equal numbers, other chambers continue to be male-dominated. The court’s swing vote, Anthony Kennedy, has hired six times as many men as women law clerks since 2005. Gorsuch, in his second term, has hired just one female law clerk.

• Harvard and Yale law schools have tightened their grip on the clerk “market,” providing half of the court’s law clerks since 2005, compared to 40 percent in 1998.

WHY IT MATTERS

The lack of diversity among clerks is important not just because it leaves minorities off the fast track to high-paying jobs. It harms law firms as well as they seek to build diverse practices, said Neal Katyal of Hogan Lovells: “The Hispanic and African-American numbers in particular are things that have long-term consequences for appellate practices.”

Crystal Nix-Hines, a partner at Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan and a former clerk to Marshall and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor said, “The credential stays with you throughout your life.” Nix-Hines said she has had “an eclectic career” that has taken her to journalism, Hollywood and an ambassadorship. Through it all, she said, “I’ve always been able to kind of re-access the legal profession in part because of my credentials.”

The lack of diversity also has consequences for the court. Though the justices and their law clerks usually downplay clerks’ importance, it’s undeniable that they wield considerable influence. One study published in the Marquette Law Review found that justices follow the recommendation of clerks 75 percent of the time when granting certiorari.

Justices have said the storytelling of the late Marshall enriched their internal debates, and a more varied cohort of law clerks might do the same. One example: Though the high court routinely takes up cases important to Native American tribes—more than a dozen petitions are currently pending certiorari—the court has never had a clerk known to be Native American.

“This is an institution that is deciding things for everyone,” said Georgetown’s Cashin. “Having a range of perspectives and experiences among the law clerks would be useful. There is an elitism and we need to acknowledge it.”

WHY SO FEW MINORITIES?

Theories abound for explaining the low number of minorities clerking at the highest court in the country. One can be summarized as the “Obama trajectory”—top minority law students like Barack Obama (first black editor of the Harvard Law Review in 1990) turning down clerkship opportunities in favor of other career paths. For the future president, heading into politics instead of clerking worked out well.

Judge Edith Jones of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit said attractive options are luring other minorities away too. “Top corporate counsel and top law firms are demanding diversity. The clients want it too,” said Jones, who has sent seven of her clerks to the Supreme Court since 2005. She added, “It may be that not all minority candidates want to become litigators or professors.”

Others point to the dysfunctional system by which federal appeal court judges hire law clerks. An orderly hiring plan that asked judges not to interview first- or second-year law students died in 2014 when more and more judges ignored it. “It’s a chaotic process” now, said Judge Margaret McKeown of the Ninth Circuit.

The resulting fierce competition has led some judges to hire clerks based on their first-year grades at law school, which Yale Law School Dean Heather Gerken said “has had a dramatic effect on our pedagogy. It makes the first year more important than it should be. Some students need a longer runway. The late bloomers don’t get a fair shot.”

The system also compels some justices to “over-book” clerks who are committed to work for them but then are asked to wait a year or more until there’s an opening. For that and other reasons, more and more candidates have multiple clerkships before working at the Supreme Court, where they’re paid $79,720.

“To be sure, former clerks are bonus babies,” said Artemus Ward, author of several books about Supreme Court clerks. “But clerking for two years in order to wait for the windfall, particularly after accruing large debts in college and law school, may seem too much to ask.”

Another trend that helps explain the lack of diversity is what Harvard Law School professor Andrew Crespo called “ideological sorting” in the clerk hiring process. Crespo, who in 2007 was elected the first Latino editor of Harvard Law Review, clerked for Breyer and Kagan.

“The more liberal justices tend to hire a greater number of liberal-leaning clerks than the conservative justices, and vice versa,” Crespo said. “If the small number of African-American and Latino applicants are also disproportionately liberal, then there may be fewer clerkship slots for which they are realistically competitive candidates.”

The late Justice Antonin Scalia used to hire one “counter-clerk” a year—a liberal who could challenge Scalia’s precepts—and some other justices did the same. But the tradition has faded in recent years. Thomas once likened the practice to “trying to train a pig. It wastes your time, and it aggravates the pig.”

So, even though most clerk hopefuls apply to all nine justices, Crespo said, “They may be realistic candidates for only some of the nine.”

Further down the clerk pipeline, some point to the “feeder professors”—most often white males—at top law schools including Harvard and Yale who recommend their favored students and research assistants for appeals court clerkships. “The real feeders are the professors,” said Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III of the Fourth Circuit, a leading feeder judge. “Some are my former clerks. If somebody gives me good people, I tend to sort of go back to them.”

Another factor is expediency, pure and simple. Busy justices rely on familiar sources who can be relied on to recommend top candidates. Supreme Court justices “have more applicants than they can say grace over,” said Judge Jones. Harvard’s Lazarus estimated that each justice receives between 1,000 and 3,000 applications yearly. “They can’t possibly go through them all and figure it out. They can’t spend the time, so it comes back to vouching” by trusted judges and professors.

Relying on a predominantly white and male feeder network undoubtedly perpetuates in-group preferences. But any suggestion that the justices bring a racial bias to the process is rejected out of hand. Jones called it a “vile charge.” And Jack White, the only African-American that Justice Samuel Alito Jr. has hired as a clerk, said, “I know he’s not a bigot. As an African-American in professional America, I know what a bigot looks like, what it sounds like, what it does. That’s not him.” White is a partner at Fluet Huber + Hoang in Virginia.

TOO PASSIVE?

Some top feeder judges have made efforts to diversify the pool of potential Supreme Court clerks. D.C. Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh has spoken several times before black law student groups.

“A big part of it is demystifying the process, having a conversation about how it works, and encouraging the students to apply,” Kavanaugh said in an interview. As a result, he has delivered 10 of his own minority clerks to the Supreme Court since becoming a circuit judge in 2006.

Especially for “first generation” law students, the tricks of the law clerk trade—like quickly becoming a research assistant for a feeder professor—are not obvious. “Law school feels very different when you are the first in your family to go there,” Crespo said. “The classrooms, the professors, the culture, can all feel a bit more foreign, and thus make law school more challenging.”

Managing the application logistics can be costly. Rukayatu Tijani, a Quinn Emanuel associate who clerked for a federal district judge in California, has launched a scholarship fund to help clerk applicants with travel costs. “Clerkship interviews can end up being really expensive, because applicants need to be ready to fly out and book a hotel room at a moment’s notice, sometimes even a day or two in advance,” she said.

The justices themselves also need to find new pathways and sources for their clerk candidates, Georgetown’s Cashin said. She recalled that Marshall recommended three African-American law clerks to Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who had never had black clerks before. Without Marshall’s recommendation, they might have been “outside the pipeline for Justice O’Connor” even though they were highly qualified, Cashin said. “The pipeline changed.”

Even without a push from justices, the numbers may grow organically in coming years. Yale’s Gerken reported that “we have 48 percent of students of color,” and in 2016, half the members of Yale’s black and Hispanic law student associations had lined up clerkships. Harvard’s class of 2020 is 45 percent students of color and 48 percent female.

But Harvard’s Crespo said the justices themselves could do more to increase minority numbers by using the bully pulpit. If the justices think clerkship diversity is good for the court and for the legal profession, he said, “The court itself is an unparalleled position of leadership to encourage other institutions in the profession to help build a diverse pipeline that leads not only to more diverse Supreme Court clerks, but to a diversification of the bar itself.” He added, “When the justices speak on issues like this, their words carry great weight.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story omitted a 2017 law clerk for Neil Gorsuch in the count of Hispanic/Latino law clerks. We regret the error. If you have information that would improve the accuracy of this study, please contact Tony Mauro at [email protected].

Karen Sloan and Maria Semmens contributed to this report. Infographics by David Palmer.