In recent months, the most prominent defense of law school as an investment has come from Case Western Reserve University School of Law dean Lawrence Mitchell, in both an op-ed published in The New York Times and an appearance on Bloomberg Law. Around the same time, Georgetown University Law Center professor Philip Schrag wrote a much more informed defense of the status quo in a review of Brian Tamanaha’s "Failing Law Schools," which will appear in a forthcoming issue of the Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. Although Tamanaha has responded to Schrag’s review elsewhere, Schrag leveled a few criticisms at an article I wrote for The Am Law Daily that I will address here.

Before I do so, allow me to summarize Schrag’s argument, which goes as follows: If the economic model of U.S. legal education doesn’t work for many students because it leaves them with low incomes against unpayable debts, the solution to their problems is the government’s Income-Based Repayment plan (IBR) and its 10-year-public-service-job sibling, Income-Contingent Repayment. Most law students can borrow up to $20,500 in unsubsidized Stafford loans at 6.8 percent interest (less a 1 percent origination fee) and cover the remaining total cost of attendance plus living expenses via Grad PLUS loans at 7.9 percent interest (4 percent fee). If they fail to find a job that pays an income commensurate to their monthly payment obligations, they can go onto IBR, which saves them from the debt peonage that would have otherwise awaited them because the government will cancel their loans after 20 years.

According to Schrag, Tamanaha reads too much into two technical terms: "Standard Repayment Plan," which is the 10-year schedule against which IBR payments are calculated, and "Partial Financial Hardship," which is the statutory definition for the financial position debtors must be in to qualify for IBR. To Schrag, few law students use the standard repayment plan anymore, making comparisons against it imprecise, and the "hardship" required to sign on to IBR doesn’t mean the debtors are living in poverty. For these reasons, Schrag maintains, IBR expands access to the legal profession for students from low-income backgrounds.

Schrag credits Tamanaha for not raising objections that I did in this Am Law Daily article. He states that "partial loan forgiveness for lower-income borrowers should be or at least will be considered for repeal because it is a public subsidy to legal education." In fact, this prediction is already proving true: Mere weeks after Schrag released his paper, Bloomberg reported that Representative Tom Petri (R-WI) was planning to introduce a student loan collection bill in Congress. The bill’s primary purpose: to cease the government’s practice of farming out student loan collections to private debt collectors, which tack on excessive fees. Petri calculates that by nationalizing the student loan collection system, the government would save $1 billion. The catch is that though the bill purports to cap total interest at 50 percent of a loan’s value at graduation, it would eliminate IBR’s loan-cancellation featuremeaning those who take on very large debts could expect to be making payments to the government into their dotage.

Post hoc developments notwithstanding, Schrag argues three points against my perspective:

(1) Critics of IBR are inconsistent because they ignore other ways the government subsidizes higher education, especially "tax-exemption for nonprofit universities, the deductibility of contributions to them, the rent-free occupancy of state land that public universities and law schools enjoy, and the direct subsidies to that state legislatures provide to public universities."

(2) Other advanced industrialized countries subsidize their legal and higher education apparatuses. IBR, at least, is progressive in that it benefits those who need relief most.

(3) Subsidies to support higher education are only one of many such investments the government makes, and they benefit purchasers of graduates’ services. Others include "food and cotton production, energy, child care, health care, flood insurance, and homeownership."

I dispute all these points and address them in order.

(1) I oppose each of the government subsidizes to higher education Schrag lists. In fact, in a previous Am Law Daily article, I argued that public law schools are unnecessary. If anyone thinks I’m inconsistent regarding the use of land tax-free by public or private nonprofit law schools, they should read my blog more often because I sometimes write there about the beliefs espoused by 19th century political economist Henry George. Although it’s beyond the scope of what I write about on The Am Law Daily, I think allowing landowners to capture increases in socially generated land values causes poverty. As one might expect, untaxed universities frequently hoard prime urban real estate, depriving municipalities of needed revenue and diminishing productive economic activity. By subsidizing higher education, government only worsens the situation. The Boston Globe‘s recent report that New England School of Law has a 30 percent, tax-free profit thanks to its over-indebted and underemployed students validates this belief.

(2) Most other advanced industrialized countries have civil law rather than common law legal systems, so subsidy comparisons aren’t apples-to-apples. Nevertheless, just because other countries subsidize higher education doesn’t mean they are right to do so.

(3) I’m against most subsidies, and just after Schrag posted his paper, even The New York Times criticized flood insurance and corporate subsidies as wasteful. Very few people defend the home mortgage interest deduction.

Identifying himself as a conservative, Schrag asks, " ‘Why not leave it to the market’? In our Internet-saturated age, if too many law graduates are chasing too few jobs, word will soon get out and fewer students will apply." Given that the Internet-saturated market forces he refers to were mainly scambloggers who call law professors con artists, Schrag must have thick skin.i Despite the ongoing nose-dive in applications, however, there’s a reasonable chance that more people will always enroll in law school than there will be jobs available when they graduate, so the market is unlikely to work as Schrag believes.

The more conservative response would not be a persistent defense of IBR but would instead be a focused attack on both Grad PLUS loans and how private student loans are treated in bankruptcy. The changes to these two aspects of the student loan system, which occurred in 2006 and 2005, respectively, have insulated many ABA law schools from a credit and enrollment crisis that would otherwise imperil them because private lenders would not be willing to lend money to law students indefinitely while the government has.ii

To illustrate, here’s the annual Stafford loan limit (subsidized plus unsubsidized) and median law school tuition, adjusted for inflation.

(Source: FinAid.org, ABA, Official Guide)

(For whatever reason, the ABA’s numbers on median non-resident public law school tuition are way off from the Official Guide‘s.)

There are a few observations that arise from this chart:

The real value of Stafford loans has dropped significantly since its 1994 peak.

In the 1980s and part of the 1990s, most law schools charged less than the annual Stafford loan limit.

Perhaps this academic year median public resident tuition exceeded the Stafford loan limit for the first time.

Starting in 1997, law students have increasingly needed to use other means to pay their tuition. Until 2006, options included savings, family contributions, Parent PLUS loans, and private loans.

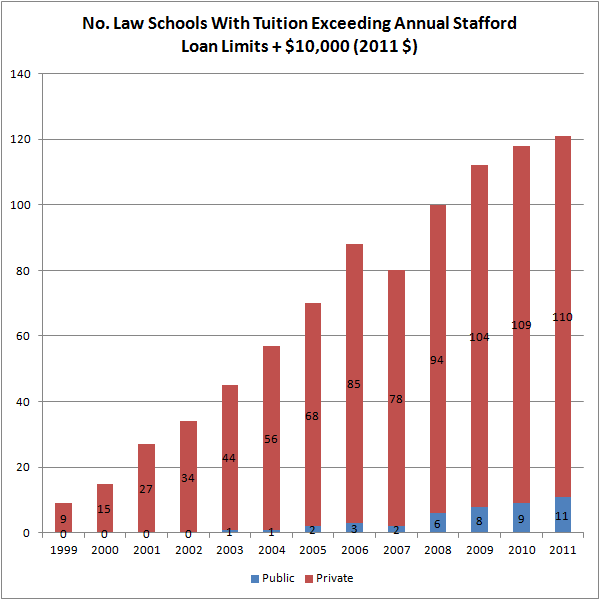

Between 1999 and 2005, the number of law schools whose tuition exceeded the Stafford loan limit by $10,000 constant dollars exploded from 9 to 70. As of today, only nine private law schools charge less than this threshold.

(Source: FinAid.org, Official Guide)

In a counterfactual world without Grad PLUS loans and dischargeable private loans, private law school debtors would have started using the bankruptcy system to deal with their unpayable loans beginning in the late 2000s. Lenders would have responded by raising interest rates, demanding cosigners, ending in-school deferments, requiring clearer data on graduates’ employment outcomes from the schools, and eventually ceasing lending to law students once they realized the low likelihood of repayment. The result: law schools with poor graduate outcomes would have curtailed their expansion and halted their tuition increases, if not shut down entirely.

Sadly, in the actual world we inhabit, the federal government has chosen to sustain a number zombie law schools that can only be killed by convincing students who pay full tuition via unlimited debt not to attend them. Even if some of these schools shutter, there’s no reason to believe that the remaining ones will reduce their tuition significantly because the nucleus of the enrollment pool consists of people willing to pay whatever law schools tell them to. Thus, conservatives who are interested in using market forces to manage law school pricing should start first with the Grad PLUS Loan Program, and then wait for inflation to erode away the Stafford loan limits.

Matt Leichter is a writer and attorney licensed in Wisconsin and New York, and he holds a master’s degree in International Affairs from Marquette University. He operates The Law School Tuition Bubble, which archives, chronicles, and analyzes the deteriorating American legal education system. It is also a platform for higher education and student debt reform.

Footnotes:

i. Schrag also concludes that reducing the professional entry barriers to providing legal services and allowing more market competition would better serve the public. Here I agree with him, and for those interested in similar discussions, I recommend reading my comment to the ABA’s Task Force on the Future of Legal Education.

ii. The "undue hardship" exception to discharging student loans in bankruptcy was extended to private loans with the October 2005 Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act, and Grad PLUS loans are a modification of the existing Parent PLUS Loan Program enacted by Congress in February 2006 via the ironically titled, "Deficit Reduction Act of 2005."