The foundation, according to its lawyer in the case, Luke Nikas of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, found itself suddenly fearing that hundreds or thousands of Warhols—often created using his famed silkscreen process that typically began with a photograph as a source—could be in danger of facing copyright infringement challenges coming from far and wide.

Meanwhile, Goldsmith—who Koeltl noted has photographed numerous musicians and performers throughout her career—responded to the foundation’s action by asking for rulings of her own. Specifically, she and her lawyers asked Koeltl to deny the foundation’s declaratory judgment request and to find that all of Warhol’s 16 Prince-image works from 1984—14 of which were created using silk-screening—do, in fact, infringe on her 1980s Prince photograph copyright.

On Monday, Koeltl, in a carefully crafted 35-page opinion, ruled in the foundation’s favor. He declared that no copyright infringement existed; and he also turned back Goldsmith’s cross-summary judgment motion requests.

Koeltl explained in the decision’s first half that he was expressly not finding whether the Warhol creations from 1984 were substantially similar to Goldsmith’s 1981 Prince photograph. He need not make that finding, he said, because it was clear that, in this case, the Warhols at issue were protected by the statutory “fair use” defense.

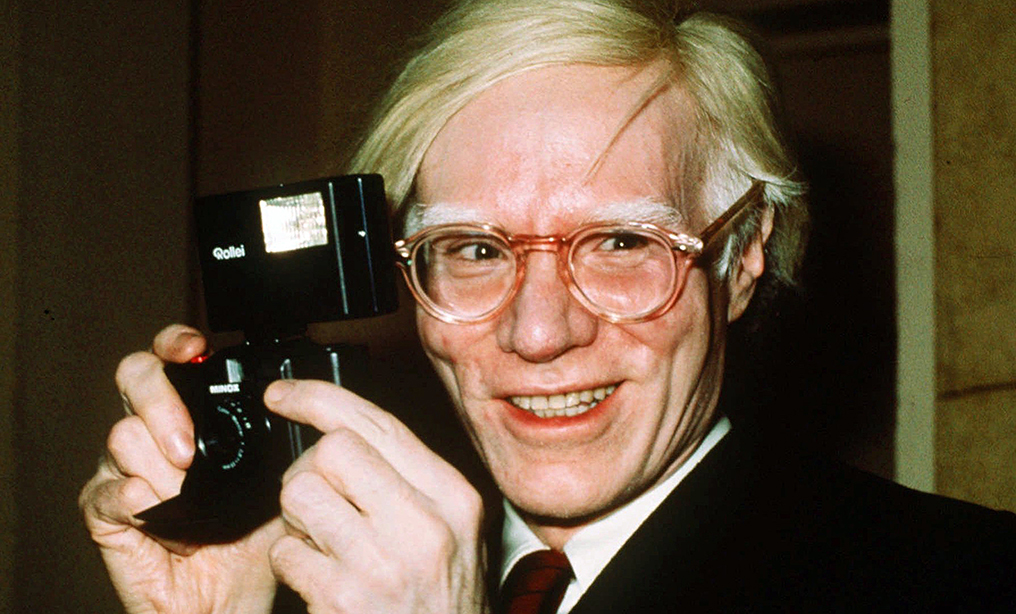

Andy Warhol in 1976. Photo: Richard Drew/AP

Andy Warhol in 1976. Photo: Richard Drew/AP