According to the U.S. Supreme Court, a patent application is one of the most difficult legal instruments that can be drafted (Topliff v. Topliff, 145 U.S. 156 (1892)). Small wonder that most patent applications are initially rejected by the Patent Office. Although negotiating with the Patent Office examiner; including presenting amendments and arguments often will lead to a patent application being issued as a U.S. patent; there are times when no amount of effort will translate into success.

The patent application process is referred to as a “pro se” proceeding, meaning there is technically only one party involved—the patent applicant. While a Patent Office examiner is being the “traffic cop” if you will—giving the red light or the green light for an inventor to get his patent—the examiner’s role is not adversarial. In the process of getting a patent, it is not as if one is “suing” an examiner. Rather, U.S. patent examiners are merely representing the public interest by determining whether the patent application satisfies the requirements of the U.S. Constitution and the federal statutes. And yet, patent examiners and patent attorneys will sometimes disagree on whether the statutes are being applied correctly. Try as they might, attorneys will sometimes dispute examiner positions, to no avail.

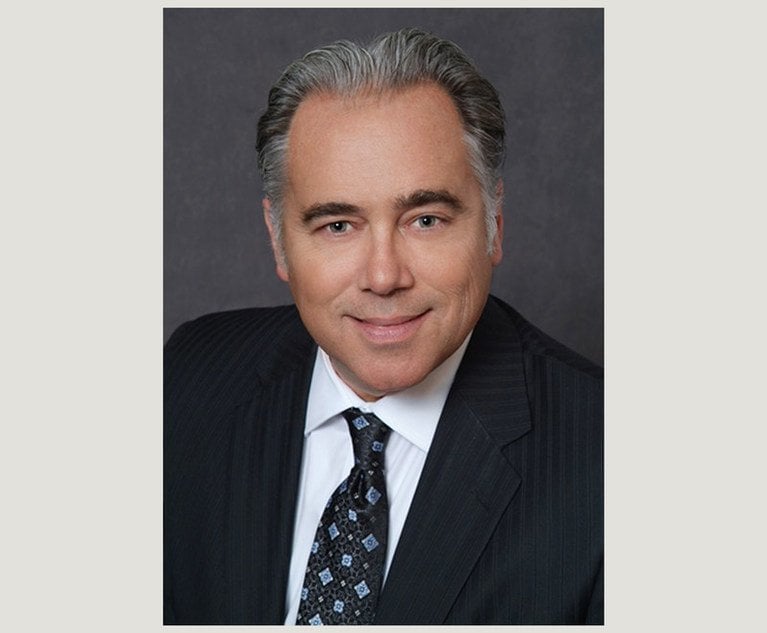

Lawrence Ashery of Caesar, Rivise, Bernstein, Cohen & Pokotilow.

Lawrence Ashery of Caesar, Rivise, Bernstein, Cohen & Pokotilow.