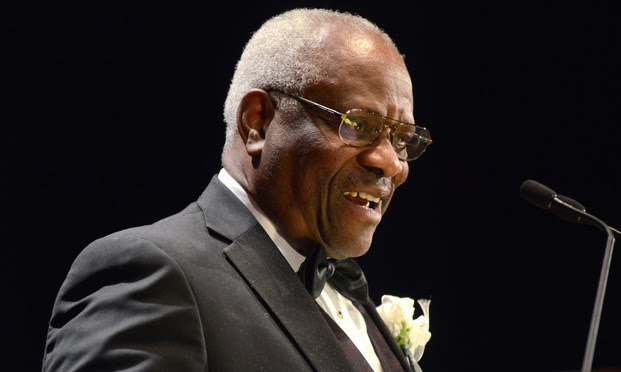

Courtesy photo

Jefferson, the first African-American chief justice of the state high court and now a partner in Austin’s Alexander Dubose Jefferson & Townsend, wants the Supreme Court to take up a fight rooted in the city of Houston’s decision to provide marital benefits to the spouses of employees regardless of whether those spouses are same sex or opposite sex.

His former court was wrong, Jefferson argues in Houston’s petition, when it held that the two U.S. Supreme Court rulings—the same-sex marriage decision in Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015 and its per curiam decision last term in Pavan v. Smith—did not resolve whether the Constitution requires states or cities to provide the same publicly-funded benefits to all married persons. The Texas high court held that Obergefell only required states to license and recognize same-sex marriages to the same extent that they license and recognize opposite-sex marriages.

“Once a state extends benefits to any married couple, it must treat same-sex couples with ‘equal dignity in the eyes of the law,’” wrote Jefferson, quoting Obergefell in his petition, City of Houston v. Pidgeon.

If the justices grant Houston’s petition, it would be the second major case involving the gay community on the docket this term, which starts Oct. 2.

The justices already have agreed to decide a case involving a Colorado baker who, citing his religious beliefs, refused to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. The baker, Jack Phillips, was found guilty of violating his state’s anti-discrimination law. And waiting in the wings with the Houston case is Evans v. Georgia Regional Hospital, which asks whether federal civil rights law bars discrimination in the workplace based on the basis of sexual orientation.

When Jefferson announced his retirement in 2013, local newspapers praised him as one of the most respected jurists in the country. He told the Texas Lawyer then: “I know there are many aspects about leaving that I’ll regret.”

“I loved being on the court,” Jefferson said Wednesday. “I felt like the timing was right. I was closing in on 13 years and had served as chief justice from 2004 to 2013. I had accomplished many of the goals I set out to accomplish. To be frank, my kids were college-age and it was time to consider whether I could help them with tuition. That’s difficult on a state salary.”

The Texas Supreme Court, he said, is an “extraordinary court” that handles only civil cases and has discretionary review. “So we could pick and choose some of the most important legal issues of the day. And also to its credit, it is very involved in access to justice issues—increasing legal aid to poor.”

Jefferson said he worked to expand legal services for the poor, bring cameras into the courtroom and adopt electronic filing for briefs.

“Lawyers who have cases pending on an issue similar to one being argued can read the briefs and watch the argument and then develop their arguments to be in tune with, or to distinguish from, what is happening in the courtroom,” he said. “It’s also great for the public. One of the problems in the United States is lack of civic education. With cameras and access to briefs, intrepid citizens to can take it upon themselves to watch and learn and hold the court accountable.”

Jefferson is no stranger to the U.S. Supreme Court. He argued and won two cases: Board of Commissioners of Bryan County v. Brown (1996) and Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District (1997).

“Bryan County was the first cert petition I ever filed and a few months later it was granted,” he said. “It was thrilling. I was 33 years old. The kind of work I do—appellate work—that’s the crown jewel. In both cases, I contacted my former professor—Charles Alan Wright at [University of Texas] and he arranged moot courts. That really helped guide me and prepare me for the Supreme Court arguments.”

Persuading the Supreme Court this time to hear his petition may be more difficult because of the Houston case’s procedural posture.

The Texas high court resolved an interlocutory appeal from a trial court’s order and remanded the case to the trial court for further consideration consistent with its judgment. “Procedurally we have to convince the court this question is cert worthy even though it was remanded for further consideration,” he said. “We’ve done our best.”

Jefferson’s firm is a civil appellate boutique. “It’s wonderful working with exceptional lawyers both as co-counsel and adverse,” he said. “The best case is a case in which the other side is represented by an extraordinary lawyer. Usually you’re fighting over grand ideas.”

And off the bench, he now can do pro bono work.

“Last term we were successful in representing indigent parties who were improperly assessed fees in divorce cases,” he said. “I’ve also chaired a commission the Supreme Court put together to expand civil legal services. Things like that are very fulfilling.”