By writing well-reasoned originalist opinions that can be evaluated on neutral grounds—such as the strength of the historical evidence or the coherence of the textual analysis—Justice Thomas has advanced the methodology of originalism in two ways. First, by providing a second originalist voice on the Supreme Court, Justice Thomas has made it impossible for lawyers and judges to ignore originalist arguments. Second, and more importantly, by writing opinions that often disagreed with those of Justice Scalia, Justice Thomas has rebutted the conventional criticism that originalism is a wooden or results-oriented methodology.

By disagreeing with Justice Scalia on originalist grounds, Justice Thomas has made clear that originalism is not a political tool for reaching “conservative” results. Some commentators have portrayed originalism as a façade jurists and academics hide behind to pursue their policy preferences. But although no methodology is immune from abuse, Justice Thomas’s opinions have established that the advantage of originalism is not that it provides a foolproof method for arriving at uniform results, but that it offers neutral principles suitable for a judiciary in a democratic republic with separated powers. By engaging in debates with Justice Scalia, Justice Thomas has focused our attention on the neutral materials in law—text and history—and weakened the criticism that originalism is results oriented. Originalism may not eliminate reasonable disagreement among jurists, but it helps to discipline legal debates.

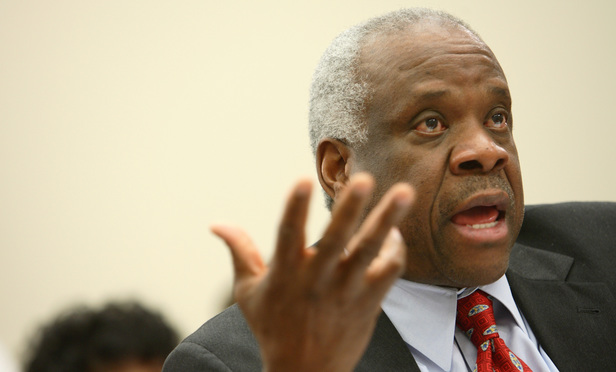

William Consovoy of Consovoy McCarthy Park and Nicole Stelle Garnett of Notre Dame Law School examined Thomas’s race-related jurisprudence. The justice’s history, they said, is critical to understanding that jurisprudence. Consovoy is a veteran high court litigator who argued Spokeo v. Robins and Evenwel v. Abbott. He is representing challengers to the admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.