There is a well-defined system in American corporate life when a business or industry sees a piece of regulatory legislation coming down the pike. If the bill seems favorable to their business, they may offer support to the legislation’s Congressional sponsors, or at least just stay out of the way. And if the bill poses a potential threat to the bottom line, publicists, lawyers, and lobbyists are deployed to try to alter or kill the bill.

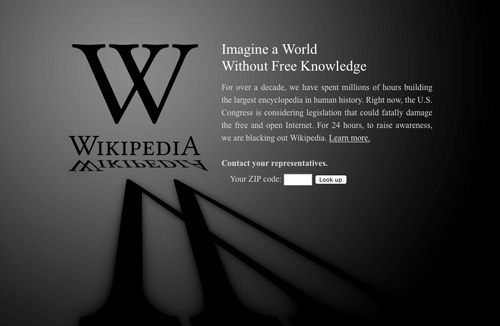

But a funny thing happened as two pieces of legislation that would affect intellectual property and the websites that may (or may not) help distribute pirated material inched closer to passage in Washington, DC. The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and Protect IP Act (PIPA) became online memes for those who were against the bills, and some of the biggest names in the Internet biz—including Wikipedia, Google, and Reddit—decided to make a direct public case, culminating in a one-day “blackout” of sites that said they’d face shutdown if the bills were enacted as written.

A day ahead of the protest blackouts on Wednesday, Twitter’s chief executive Dick Costolo made it be known in blunt terms that his business would not be participating in the anti-SOPA activities. “Closing a global business in reaction to single-issue national politics is foolish,” he said.

Certainly not everyone in the web industry followed Wikipedia’s lead in blocking access to their content and services as a way to highlight their stance against SOPA and PIPA, which, by many accounts, employ drastic measures to curtail copyright violations and allow for certain websites to be penalized by being unilaterally blocked.

But many did brandish their solidarity prominently, foolishness be darned. Google blacked out its brand name on the search engine’s heavily trafficked home page. Wired.com blacked out all of its headlines and teasers on the magazine’s site. Mozilla joined in the “virtual strike” by darkening its home page and displaying the message, “Protect the Internet: Help us stop Internet censorship legislation.”

Was there, then, a good business case to be made for the protest?

Tim Wu, a Columbia University law professor and author of Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires, says yes: It boils down to a battle for survival. “Google and other web companies live or die based on how open the Internet is,” he says, calling an open Internet the natural environment that has allowed online businesses to thrive.

In the short term, it might not look like a good idea for top sites to cripple themselves for a day. Wu surmises that would contravene typical advice about not alienating customers. “Generally, companies don’t protest,” he says. “I think the usual business school textbook would say: it’s better to stay away from contentious political issues.”But in the long term, Wu says, the protest moves make sense given the consequences of the outcome. The IT community and copyright holders in the entertainment industry—i.e., Hollywood—are fundamentally opposed systems. Hollywood operates on the basis of closed networks—e.g., television, radio, or cable. Consumers don’t “put stuff up” on cable or network television, for example, the same ways users freely upload content to the Web, Wu says.

Web industry products, on the other hand, are born of open networks and open protocols. “They build better software than anyone else in those environments, and no one can compete with them,” Wu says.

For both sides in the SOPA/PIPA battle, then, defending their ground is critical: “Companies are fighting for territory, and they’re trying to make the territory as hospitable to themselves as possible,” Wu says. “I think everyone knows, at a bottom level, the more open the nation’s communication systems are, the better it is for Silicon Valley. The more closed, the better it is for Hollywood. That’s just a fact of life.”

He adds, “Whoever converts territory to their basic home turf wins.”